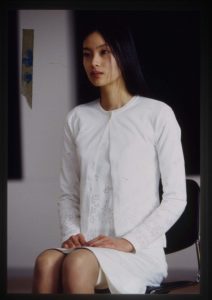

Ôdishon / Audition (1999) begins when widower Shigeharu Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi) confesses to his film producer friend that he’s struggling to meet women. This friend, Yasuhisa Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimura), convinces him to set up a series of auditions for female leads in a new film. However, the film does not exist, and the auditions have a different purpose: to find Shigeharu a new bride. Beautiful, but also meek and reserved, Asami Yamazaki (Eihi Shiina) fits the bill. When she auditions, Shigeharu falls fast and hard for her, a passion that Asami politely welcomes.

I know. So far you are thinking, this doesn’t sound like a horror film. This certainly doesn’t sound like ‘one of the most notorious J–horror films ever made’, to quote Arrow’s Audition Blu–ray release.

So, what is it about this film that makes it so scary? And why are we still talking about it, over twenty years after its initial release?

The first reason is the film’s director, Takashi Miike. Miike’s career began in Japan in the late 1990s in television and video–cinema. He is a prolific filmmaker, and prior to Audition had already directed over thirty films, v–cinema productions and television shows. Since Audition he has continued to work extensively in popular genres, mixing extreme cinema such as Visitor Q (2001), with yakuza films, musicals, jidaigeku and… children’s films. He has now made over 100 films and shows no signs of slowing down. However, Audition was his global breakout hit, and the first of his films to be seen widely outside of the festival circuit.

The press coverage of theatrical screenings then provides the second reason for the film’s infamy. The press delighted in reports of the effects that the film had on its audiences, an intense, visceral response on par with the alleged fainting and walk–outs accompanying Julia Ducournau’s Titane (2021). The Guardian and Sight and Sound both reported audience members walking out of the Rotterdam festival screenings, hissing ‘you’re sick’ at Miike, while the Mirror reported two people passing out and upwards of twenty walk–outs a night at the film’s Dublin run. The film reviews themselves did not improve its reputation: the Daily Mail branded it ‘revolting’ while The Evening Standard called it ‘the grimmest exploitation of sadistic violence I have seen in months’, thus creating the kind of furore that most film distributors can only dream of.

The third reason we still talk about this film comes down to timing. Audition broke out internationally at a unique time in film distribution and film branding. At the end of the 1990s, and in the early 2000s, anglophone territories had unprecedented access to Japanese genre film production. A series of festival and industry screenings in 1999 and 2000 led to British theatrical and video/DVD releases for Audition, Hideo Nakata’s Ringu / Ring (1998) and Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000), leading eventually to Tartan’s Film’s ‘Asia Extreme’ branding.

This was also part of a bigger cultural and technological shift in home viewing practices. As Chi–yun Shin explains, from the end of the 1990s, it was much easier to buy region-free or multi-region DVD players, and there was a ‘proliferation of international mail-order websites’, at the same time, Tartan took this further by infiltrating ‘mainstream audiences’, high street shops such as HMV, and major shopping sites such as Amazon. This meant that, just at the time of Audition’s release, a lot of film fans in Anglophone territories were starting to watch contemporary Japanese (and Thai, South Korean and Hong Kong) genre films for the first time, discovering the word of East Asian film directors such as Park Chan–wook, Kim Ki–duk and Kim Ji–woon.

The fourth reason Audition endures was because of just how the film did horror. When Audition came out, it did not follow the narrative or visual patterns of what global audiences understood by ‘Japanese horror film’. Which, at that point, was Ring. Tom Mes explains, ‘Audition was intended to be both a cash-in on and a departure from the horror boom that had swept Japanese cinemas after the success of Hideo Nakata’s Ring’. Audition was released in UK cinemas six months after Ring, which became its benchmark for comparison. As Daniel Martin reveals in his study of the UK reception of Audition, ‘while Ring unified critics, who established a general consensus that the film’s restraint was to be admired, Audition had a polarising effect on those who wrote about it’. He explains, ‘the bloody violence of Audition was either the very substance of its merit, or the proof of its worthlessness’. While Audition may contain a vengeful young woman with long black hair, there is no supernatural angle, no deep well containing dead bodies, and certainly no haunted videotape. Instead, we just have unrelenting, quiet ultraviolence, a happy, calm girl trilling ‘deeper, deeper’.

Which brings us to the fifth and final reason why Audition has endured: that remarkable genre shift. For most of its running time, Audition reads as a light–hearted comedy (albeit with disturbing cutaways to writhing sacks and dog food bowls). Then, ten minutes before the end, we switch abruptly: we abandon comedy in favour of torture. Our leading man is paralysed, a hunk of meat to be poked and prodded (and much worse). This isn’t Shigeharu’s romantic comedy, this is Asami’s theatre of cruelty. The film has not delivered what it promised. It has not taught us the audiovisual or narrative cues to account for this change in action and image.

In short, we have not been trained to look away.

This is the most shocking thing of all.

I’ve given you five reasons why Audition endures, and why it is now understood to be such a ‘notorious’ horror film. However, it is worth noting this is not how the director categorises his film. As he explained in a 2001 interview with Midnight Eye, ‘Audition is not a horror…it’s a story about a girl who has slightly strange emotions, so it’s not impossible to understand her. She just wants the person she loves to stay by her side’.

A love story or a sadomasochistic horror show? You decide.

Reading

Oliver Dew, ‘“Asia Extreme”: Japanese Cinema and British Hype’, New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 5.1 (2007)

Daniel Martin, Extreme Asia (Edinburgh University Press, 2015)

Tom Mes, ‘Audition’, in Justin Bowyer (ed) The Cinema of Japan and Korea (London: Wallflower, 2004)

Tom Mes and Sato Kuriko, ‘Midnight Eye Interview: Takashi Miike’ (2001). Available from: http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/takashi-miike/

Chi–yun Shin, ‘Art of Branding: Tartan “Asia Extreme” Films’, Jump–Cut 50 (2008), https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc50.2008/index.html

Related Articles