CONTAINS SPOILERS

Class, sex, and betrayal come to a boil in the Florida Everglades in John McNaughton’s Wild Things (available on UHD and Blu-ray), a 1998 film that has risen above the wave of adult thrillers that dotted the box office landscape in the ‘90s because of its deceptively clever script, palpable setting, and unapologetically adult themes. In the wake of the massive success of Basic Instinct, every studio in Hollywood opened their wallets for films about sexually active people with a penchant for murder, but history has forgotten films like Color of Night,Body of Evidence and Jade for a reason. Why has Wild Things remained popular and actually grown in esteem in the two decades since its release while so many similar films have had the longevity of a one-night stand? Of course, it would be naïve to ignore the horny elephant in the room and dismiss the ticket-selling threesome scene that got so many people talking, but that kind of titillation is short-lived. There’s more than a ménage a trois to the legacy of Wild Things, a film with enough simmering under the gorgeous surface to keep people talking for years.

To the rhythm of a perfect score by George Clinton (not the Parliament Funkadelic one, for the record, although anyone could be forgiven for presuming it was given this composition), Wild Things opens with a shot of an alligator rising to the surface, visually foreshadowing a film about deadly creatures hiding in plain sight. The credits then unfold over a drone shot through the gorgeous, rich Miami suburb of Blue Bay, almost as if writer Stephen Peters, cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball (who also shot Top Gun and True Romance, among many others), and McNaughton are asking viewers to imagine how many alligators are hiding under the surface of this perfectly manicured community.

The film opens properly with a school assembly that introduces its main quartet of characters: high school guidance counselor Sam Lombardo (Matt Dillon), rich girl Kelly Van Ryan (Denise Richards), troubled teen Suzie Toller (Neve Campbell), and detective Ray Duquette (Kevin Bacon). It’s not long before Kelly has accused Lombardo of rape, a claim that grows in believability after Suzie echoes it by saying that Sam did the same thing to her. At Lombardo’s trial, Suzie cracks, admitting that the girls made it all up, accusing Kelly of concocting the scheme. The disgraced counselor sues the Van Ryan clan for defamation, settling for $8.5 million, and then the whole film takes a hard right turn from what could have been a domestic drama about false accusations into something very different with the pop of a bottle.

In a sleazy Everglades motel, Kelly and Sam celebrate with champagne, a prop that was originally supposed to be a sex toy, believe it or not, which would have arguably taken a scene that was already pushing the envelope for conservative America into walkout and maybe even protest territory. As they’re celebrating, Suzie emerges from the shadows, revealing not only that she was in on the robbery of the Van Ryan fortune but that she’s intimate with both of her conspirators. Of course, no one here can run off into happiness from this point. As Ray says later, “It’s hard enough for one person to keep a secret, let alone three.” After roughly a dozen twists, the audience learns that Ray has a few secrets of his own too. And everyone but Suzie will end up dead, victims of their own greed, and, more importantly, underestimating a girl from the wrong side of the tracks.

There’s a class commentary embedded in Wild Things that a lot of people miss. In fact, McNaughton claimed that it was his most political film for this reason—because :the girl from the trailer park takes ‘m all down.” She gets revenge on the cop who saw her friend as disposable; the guidance counselor who cared more about his bottom line and his libido than his students; and the socialite who was willing to discard her for mommy’s purse.

Suzie herself draws a line between her story and a classic one in her final scene with Sam, where she’s murdered both him and Ray in cold blood. She asks him how Medea killed King Creon before she sailed way on the Helios, and even big dummy Sam knows that the answer is poison. But the arc of Medea is embedded in Wild Things in more than just this name drop. In 2010, John Thorburn wrote an essay titled “John McNaughton’s Wild Things: Pop Culture Echoes of Medea in the 1990s,” in which he draws the lines between not only Medea & Suzie but Phaedra & Kelly and Hippolytus & Sam. Of course, Hippolytus hinges on a false accusation of rape, and the title character is exiled much like Sam is from Blue Bay. Suzie herself goes through a resurrection and reclamation that echoes Medea’s, and the actual reference to end the film allows for a deeper reading of everything that came before.

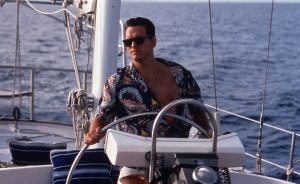

Of course, Wild Things hasn’t sustained primarily for fans of the classics. It’s main draw, beyond its provocative twists, is its incredible use of setting. So many of the Fatal Attraction and Basic Instinct riffs take place in non-descript bedrooms or seedy bars, but McNaughton carefully uses Blue Bay as a character in the film. It’s a sweaty film that takes place almost entirely outside. One can feel the heat and humidity of the Florida air in almost every shot, the sound of cicadas buzzing in the background. McNaughton always recognized the importance of setting, using the dingy underbelly of Chicago in his excellent Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer to great effect. The fact that Wild Things takes place in a world that feels real and tactile adds greatly to its impact, making the ridiculous actions of the characters more believable because they take place in a world that feels three-dimensional.

Finally, casting helps a film like Wild Things sustain a prominent place in the pop culture swamp of the ‘90s erotic thriller. Campbell was coming off the smash success of Scream (1996) and used Wild Things to continue her pivot to more adult roles after becoming known on teen drama Party of Five. Richards had made heads turn the year before in Starship Troopers and was looking for a bigger breakout, which she got in Wild Things. Bacon was arguably the biggest star in the film—excluding a wonderful supporting ensemble that includes Theresa Russell, Robert Wagner, and a fantastic Bill Murray—but it was a major part of the comeback of Matt Dillon, who would release this and There’s Something About Mary in the same year, and he’s perfectly cast in both. One can only imagine the version of Wild Things that was set to star Robert Downey Jr. as Sam Lombardo, a film that might have played more into that star’s tabloid-dominating dark side than the goofy idiot version played by Dillon, or how the film might have been perceived then and now if the final twist that Sam and Ray were a couple had remained intact.

Wild Things was mostly sold on the image of deadly women that dominated adult thrillers in the 1990s—the tagline on a poster with the two female lead with their heads barely above water was “They’re dying to play with you.” The tawdry aspects of the film led to three cheap sequels that mostly repeated the twists with none of the personality: Wild Things 2, Wild Things: Diamonds in the Rough, and Wild Things: Foursome. None of those had the impact of Wild Things, a film that surfaced like an alligator, took a bite out of pop culture, and slinked below the water again, but never really left.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RbnGi43LqI4