by Beatrice Loayza

The `60s and `70s were a radical time for American cinema, an explosion of sex, violence, and moral ambiguity that reinvigorated Hollywood for younger audiences in the throes of revolutionary fervour. Jack Hill, the cult icon perhaps best known for his blaxploitation films with Pam Grier, is not likely the first name that comes to mind when thinking of the particular generation of filmmakers who began their careers working under legendary indie producer Roger Corman (among them Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, and Francis Ford Coppola). Yet no one embodied the era’s iconoclasm quite like Hill. His movies—and filmmaking practices—went against the grain of the studios, and white, bourgeois America at large: they depicted joyous feminist uprisings, complex Black characters, solidarity among the marginalised and working classes.

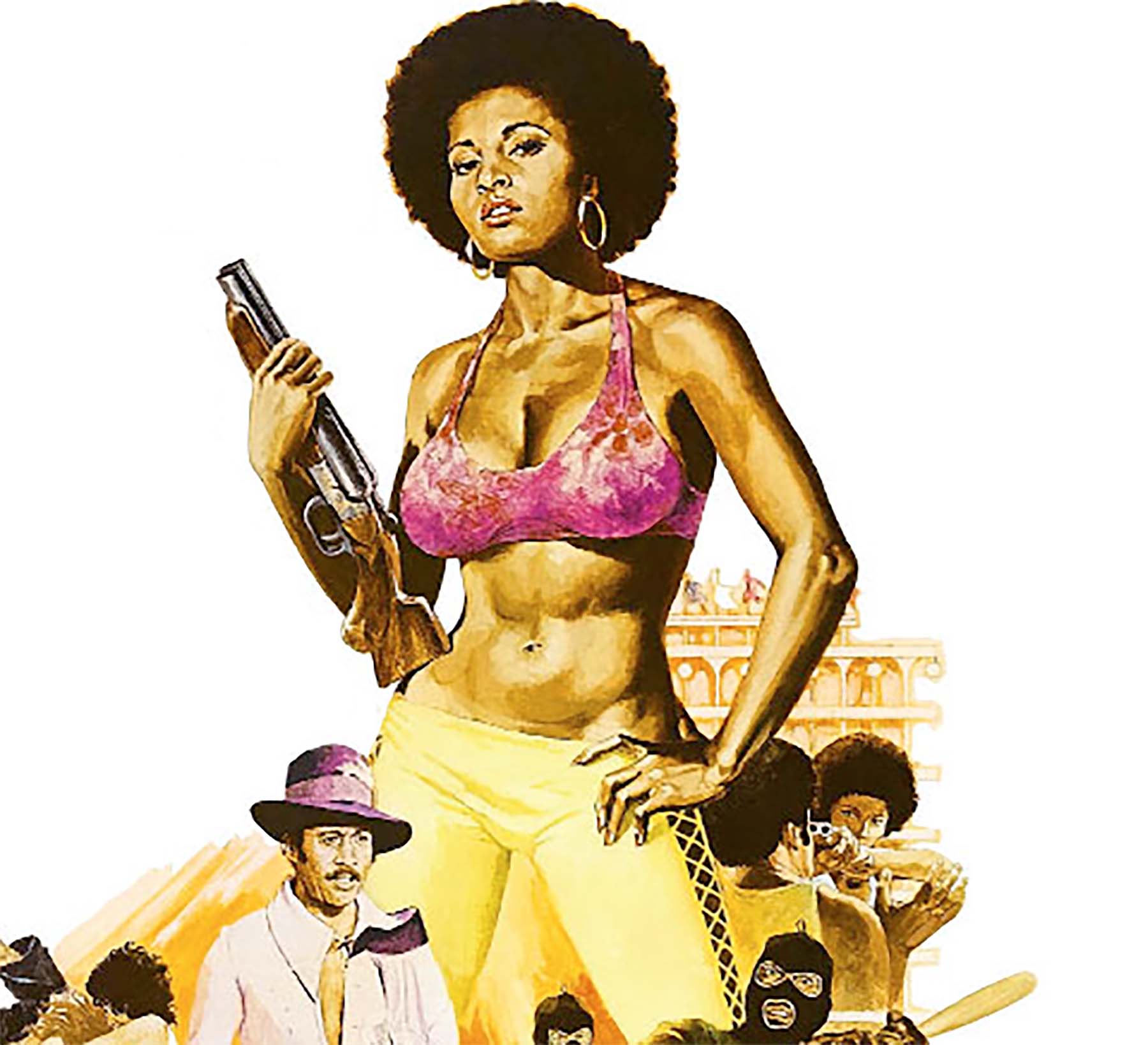

Hill also hired Black talent behind the camera—technicians, assistant directors, and stuntmen (like Bob Minor). His role in recruiting Black actors like Grier in unexpectedly lucrative hits like Coffy also upended expectations about the appeal of Black stars, and the kinds of characters and stories capable of exciting both Black and white audiences.

Nevertheless, critics loathed his movies. They were trashy, lewd, cheap—descriptors that many at the time applied to several now-canonized New Hollywood titles. In any case, such insults weren’t exactly wrong. These were cheap movies, and yes, they revelled in trashy daydreams and nightmares: rape and nudity, murder and fast cars, girls with guns and hyperactive libidos. This was the world of low-budget “B-movies” that Hill inhabited. On the surface, his movies were dime-a-dozen exploitation flicks, produced en masse to appease the leering youngsters who swarmed the drive-ins. Dismissed as such, Hill felt at liberty to weave in boldly political messages that often commented on the very sex and violence on display. In a 2014 interview with Dazed Magazine, Hill attests to this artistic freedom:

“I feel quite fortunate that I worked in the low-budget sector because it meant I did not have to deal with committees who wanted to impose their ideas and prejudices on my material. I had a free hand – much more so than I would have had if I was working for the studios. As long as you put the elements in there that producers like [Roger] Corman knew they could sell, such as sex and violence, you could raise the picture a little bit higher than they expected and give the audience something intelligent to chew on.”

While studying film at UCLA, Hill befriended fellow student Francis Ford Coppola, who—having already begun a working relationship with Corman—brought Hill into the producer’s orbit. The two young men had collaborated together before, on The Bellboy and the Playgirls—a bizarre skin flick that intercut footage from a black and white German movie with new color footage of nude women shot by Coppola, and edited by Hill. Then, early on under Corman, Hill was a co-director of sorts: he was assigned to add 20 minutes to Corman’s The Wasp Woman so that the producer could sell it to TV; Hill shot bits and pieces of The Terror, along with Coppola, Monte Hellman, Denis Jacob, and Corman himself; meanwhile Blood Bath was originally completed by Hill, but Corman brought Stephanie Rothman on board to write new scenes and do re-shoots. This was the kind of nutso moviemaking that defined the Corman “film school.” Not only was the collective effort of film production taken to an absurd extreme, movies could be cobbled together from the unwanted scraps of other movies.

Hill’s debut, Mondo Keyhole (1966), a grim, sleazy shocker about a serial rapist, certainly made for a bold first feature. But it was Spider Baby (1967; technically shot before Mondo, but released years later) that teased Hill’s fascination with difficult women and collective revolt. Positioned somewhere between the The Addams Family and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Spider Baby is a brilliant and strangely heartfelt balancing act of humour, scares, and sex appeal. The story follows a trio of orphaned siblings and their loyal chauffeur (played by Lon Chaney, Jr.) who must fend off distant cousins claiming ownership of their family home. The “kids” suffer from a rare genetic disease that causes them to act out violently, yet audiences come to sympathize with the sinister youngsters. We can’t help but applaud this group of violent weirdos defending their deranged, but happy, way of life from the threat of domesticated normalcy.

In Pit Stop (1969)—perhaps Hill’s most visually and emotionally striking film, at least according to this viewer—a lone drag racer enters the wild world of figure eight racing, fighting and hustling his way to the top with ultimately no regard for the lives of others. Before the film reaches its devastatingly grim conclusion, our protagonist, Grant (Brian Donlevy), has a kind of makeshift family of groupies and competitors-turned-teammates. When Grant prioritizes his own desire to be the best, he renounces the value of these relationships and rejects his part in the community. Life is lonely at the top.

Two years after Pit Stop, Hill spearheaded what would become one of the biggest hits for New World Pictures, the production and distribution company founded by Corman in 1970. The Big Doll House, which features Pam Grier’s breakout performance, is Hill’s stab at the women-in-prison subgenre, an obscene sleazefest complete with lesbian sex scenes, dominatrix-like prison guards, and girl-on-girl mud wrestling. Set in the jungles of the Philippines, female inmates are victims of a cartoonishly villainous regime, subjected to cruelty and torture before realising that there is strength in numbers and blasting out of their chains, with guns a-blazing. The film (as with Hill’s women-in-prison follow-up, The Big Bird Cage, 1972) doesn’t stray terribly far from the campy trappings of the subgenre, yet Grier’s performance in particular grounds the spectacle with nerve and grit that imparts fury without negating her sensuality.

Grier eventually busted out of prison and took starring roles in Hill’s subsequent blaxploitation films, Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown(1974). The actress plays a female vigilante in both films, wielding her sexuality and taking justice into her own hands against drug dealers and mob bosses terrorizing and killing her neighbours and loved ones. The authorities, despite their concrete morals, are shown to be incapable of protecting the community; laws are feeble and ineffectual, Hill seems to say, against the deeply rooted misogyny and racism that plagues our communities. Grier is indubitably the star, and the primary ass-kicker, yet she is also shown to be a revolutionary leader of men and women—a role that other female characters will take on in Hill’s coming work. In Foxy Brown, for instance, Grier’s Foxy turns to a group of Black radicals and neighbourhood watchmen for support against a band of armed cronies.

Hill has a much lighter touch in his teen sex comedy, The Swinging Cheerleaders (1974), about a feminist journalist who infiltrates a cheerleading squad to report on its retrograde sexual politics. Eventually, our heroine realizes there are bigger fish to fry in a betting conspiracy orchestrated by a group of shady school administrators. The most sexually liberated of her fellow cheerleaders, she ultimately leads members of her squad, as well as a few football players, in a raid against these corrupt authorities.

Hill’s interest in collective struggle reaches its apotheosis in his penultimate film, Switchblade Sisters (1975), a fiercely feminist work that waves the flag of women’s solidarity while never indulging in sexual explicitness for its own sake. The film not only traces the dissolution of a girl gang subordinate to its male gang counterpart, and the establishment of a new, more enlightened and autonomous girl gang—the “Jezebels.” It also envisions radical intersectional collaboration when these white girls turn to an all-female group of Black militants for help in defeating a common male enemy.

Hill never considered himself an auteur or a serious filmmaker, yet, intentionally or not, his outlandish low-budget movies captured the radicalism of the times without didacticism, and across boundaries of race, class, and gender. Hill was decades ahead of his time in terms of the subjects and kinds of relationships he committed to screen, and the diverse audiences he courted in the process. Most impressively, he made it look easy.