While the tradition of twisted storytelling through sequential art can be traced back as far as the 12th-century in Japan — the Heian-period tale of emaciated spirits who lick spilled water in temple cemeteries, Gaki Zoshi (Scroll of the Hungry Ghosts) — horror manga as we know it today didn’t really take off until much later. In fact, it wasn’t until Asahi Sonorama’s Monthly Halloween magazine was established in 1986 that horror finally had a dedicated home in mainstream manga — with rival publications Susperia and Strange Stories of Sleepless Nights following soon thereafter.

Monthly Halloween was the original home to such classic stories as Junji Ito’s Tomie (1987-2000) — one of many disturbing narratives to since work its way onto the silver screen. But even before the late ‘80s horror manga boom, tales of madness and depravity had lurked the sidelines of print publications, later become a blueprint for brazen and bizarre feature films.

See Hideshi Hino’s niche 1968 one-shot Doll ningyou, published in avant-garde magazine Garo, which followed a group of disabled children disfigured from a world of smoke and pollution. Shigeru Mizuki’s 1960-169 series GeGeGe no Kitarō (Kitarō of the Graveyard) concerned the last survivor of the Ghost Tribe and his adventures with folkloric spirit-creatures known as yōkai. And Kazuo Umezu, regarded as one of the progenitors of the contemporary horror manga genre, penned the likes of Kuchi ga Mimi made Sake-ru Toki (The Moment The Mouth Tears to Ears), Hito-kobu Shoujo (A Girl Who Has A Human-faced Lump on Her Cheek) and the 1972-1974 series Hyōryū Kyōshitsu (The Drifting Classroom) — concerning a school mysteriously transported an apocalyptic future; later adapted to film by Hausu’s Nobuhiko Obayashi.

Umezu was also the writer of a pair of mid-‘60s manga stories that would become the basis for a brilliant and under-appreciated Daiei horror film directed by the original Gamera series maestro Noriaki Yuasa: 1968’s The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch. And in many ways, this black-and-white tale of laboratory experiments, spooky dream sequences, watchers-in-the-attic and Onibaba-esque demons foreshadows much of the horror works that define Japan’s Y2K horror boom. Full of trippy visuals and ambitious practical effects (not to mention a dizzyingly theatrical climax), it’s a fitting entry point for a vivid world of visually captivating films that have their origins in the most twisted of manga tales.

As this list no doubt proves — when it comes to good film source material, often illustration speaks much louder than words.

Flower of Flesh and Blood (Hideshi Hino, 1985)

In 1991, American actor Charlie Sheen took his copy of the 42-minute Flower of Flesh and Blood to the authorities, convinced he had watched a real-life murder take place — sparking a full FBI investigation into manga artist Hideshi Hino’s film, and the rest of the Guinea Pig horror series.

The film — which concerns the abduction, murder and dismemberment of a woman by a man dressed as a samurai — was fake. But the legendary torture-porn prototype, and its series siblings, remain impressively vivid in their depiction of violence and depravity — each shot in cinema verité style using all manner of fun physical effects.

Hino directed two entries in the series, each based on his own grisly manga stories — with 1988’s Mermaid in a Manhole joining four other imaginative titles in the Guinea Pig canon: The Devil’s Experiment, He Never Dies, Android of Notre Dame and Devil Woman Doctor.

The Guyver (Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang, 1991)

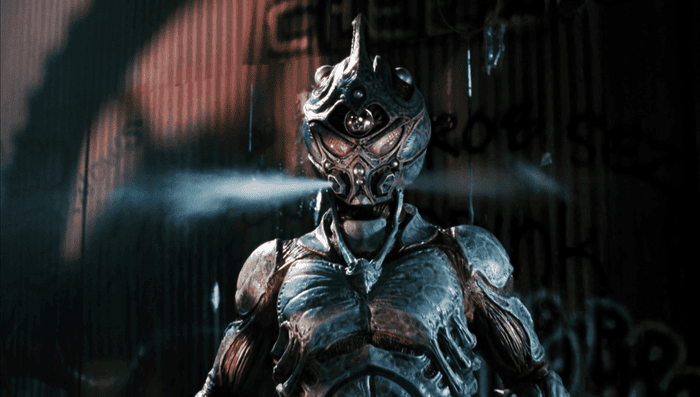

This impossibly entertaining American adaption of Yoshiki Takaya’s 32-volume (and counting) Bio-Booster Armor Guyver manga series stars a post-Star Wars Mark Hamill in a leading role — but the real draw comes from the fascinatingly silly sci-fi plot and an array of outstanding creature designs.

The opening scroll details biological super-soldiers called Zoanoids, a villainous corporation called Chronos, and, of course, the star of the film: an alien armour that can proliferate a human’s natural powers to transform them into ‘The Guyver’. By the mid-point, the film descends into chaotic brawls in warehouses between various men-in-suits — which is absolutely to the film’s merit, because but they all look fantastic. From bipedal alligator-men to demonic gremlins; elephant-nosed henchmen and, of course, the titular alien Power Ranger — The Guyver never ceases to be enjoyable.

Co-director “Screaming Mad George” made his name as a visual effects artist on Predator, Big Trouble in Little China and Beyond Re-Animator — and his pedigree is made evident here. The latter series’ Brian Yuzna and Jeffrey Combs, both bring their own b-movie charm to The Guyver, — as producer and actor, respectively.

Uzumaki (Higuchinsky, 2000)

Junji Ito began writing manga while he was working as a dental technician in the mid-‘80s — today he is widely regarded as one of the foremost horror mangaka in Japan, thanks to the international popularity of critically-acclaimed series’ such as Tomie, Gyo and Uzumaki.

Influenced by the works of Kazuo Umezu and Edogawa Ranpo, as well as films like The Exorcist and Suspiria, his manga works are known for their Lovecraftian tropes and grotesque and monstrous art style. No surprise, then, that several of his collections were adapted to cinema at the height of the J-Horror boom.

The most notable of these was a duo of films directed by Higuchinsky. TV movie Long Dream was a fittingly weird, low-budget adaption of a short story concerning a hospital patient who loses the ability to distinguish between fiction and reality. More well-known is Uzumaki, the slime-green tinted J-horror classic about a town afflicted by spirals that cause obsession, insanity and death among the townsfolk.

The events within say it all: a slow-moving school student appears to be transforming into a snail, while the protagonist’s boyfriend’s father (played by Audition and Hana-bi actor Ren Osugi) becomes enthralled by the washing machine. Even the direction emphasises vortexes, with shots fixating upon spiral staircases and spinning police truncheons. It all makes for an extremely zany, but thoroughly memorable yarn that remains true to the brilliant source material throughout.

Ichi The Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001)

In truth, you could stick your arm deep into a bucket full of Miike’s 100-or-so films and chances are you’d come out with a film adapted from a manga. But less easy to predict would be what flavour of film you’d find yourself with.

It might be Mars colonisation sci-fi Terra Formars (2016), adapted from Yū Sasuga and Kenichi Tachibana’s 22-volume serial. It could also be un-killable samurai romp Blade of the Immortal (2017), which ran for nearly twenty years in manga form. As The Gods Will (2014) was Miike’s return to horror in 2014; a high school game-of-death story based on a two-part manga series. And the Crows series (2007-2014) was based on the teen delinquency story penned by Hiroshi Takahashi in the ‘90s.

But the cult director’s most infamous manga adaption is surely 2001’s Ichi The Killer. The ultra-violent cult classic made Tadanobu Asano an international icon for his portrayal of the mutilated and sadistic gang enforcer Kakihara, on the hunt for the psychologically unstable killer who murdered his boss. Notorious upon release, the film was heavily censored by the BBFC for scenes of perverse violence and torture. Hideo Yamamoto was the brainchild of the whole torrid tale, including the iconic, slit-mouthed lead.

Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

You’ve seen the film — but did you know that this pinnacle of Hallyu cinema is actually an adaption of a popular mid-‘90s Japanese manga?

It’s true — though Park Chan-wook’s version takes some considerable liberties with the story, after building from Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi’s original premise of a man emerging from a long, unexplained imprisonment. Park’s adaption, shot in Busan rather than the manga’s Shinjuku Golden Town, is considerably more brutal than the source material — with Choi Min-sik’s hammer rampage a notable addition to the film’s story.

The nuances of the filmic conclusion were also entirely unique to the cinematic adaption — making Park’s live-action Oldboy clearly the more twisted incarnation of the tale.

Tokyo Tribe (Sion Sono, 2014)

Sion Sono’s done it all — absurdist J-horrors, postmodern pinku eiga, kaiju comedies and four-hour upskirt opuses all a part of his increasingly brilliant canon of work. But one of his craziest works, no doubt, is 2014 hip-hop gangster musical Tokyo Tribe.

Adapted from the long-running Tokyo Tribes manga by Santa Inoue, Sono’s live-action movie fuses the gang warfare of The Warriors into a dystopian society akin to Burst City — only instead of punk bands and concrete rubble, it’s all neon lights, gold chains and urban beat-downs. A majority of the dialogue is delivered in the form of rap verses from the film’s numerous warring hip hop gangs — with the whole façade kicked off by an elderly turntablist in Tokyo’s back-alley slums.

At the centre of it all is a magnificently over-the-top performance from Riki Takeuchi (Dead or Alive, Battle Royale II) as the lecherous Lord Buppa — a cannibalistic crime lord with a passion for women and machine guns. What’s not to love?

Tezuka’s Barbara (Macoto Tezka, 2019)

Osamu Tezuka was the legendary cartoonist responsible for Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion — but in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, he moved away from child-friendly animations in favour of more adult-orientated works. The erotic and psychedelic Animerama films A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra might be considered anime’s answer to the pinku eiga, or softcore “pink film”. Barbara, on the other hand, was long considered “un-filmable” due to its sexually charged subject matter.

Nonetheless, Tezuka’s own son Macoto — director of 1985 cult classic comedy-musical The Legend of the Stardust Brothers — would adapt the controversial manga himself in 2019 for what would have been his father’s 90th birthday. A mysterious noir concerning a troubled writer and his muse, the brooding Tezuka’s Barbara channels Lynchian and Kubrickian influences to deliver one of the strangest Japanese films of the year.