Parasite may have been the film that won South Korea its first ever Academy Award, but as any cineaste will testify, the country’s most significant international filmmaking breakthrough had already occurred some sixteen years prior.

2003 was a watershed year for South Korean filmmaking. Bong Joon-ho had landed his first hit with Memories of Murder — winner of Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor at the Grand Bell Awards — while Kim Jee-woon would release A Tale of Two Sisters, a Kubrickian masterwork that became the first Korean film released in US theatres. But even more significant was a darkly comic and creatively shot revenge thriller by Park Chan-wook that combined brutal violence with lashings of Hitchcock, Fincher and Oedipus Rex. Oldboy was the fifth-highest grossing film in Korea that year, and, after taking home the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2004, it would return an unprecedented $15m worldwide as international critics and cinema-goers pounced on it.

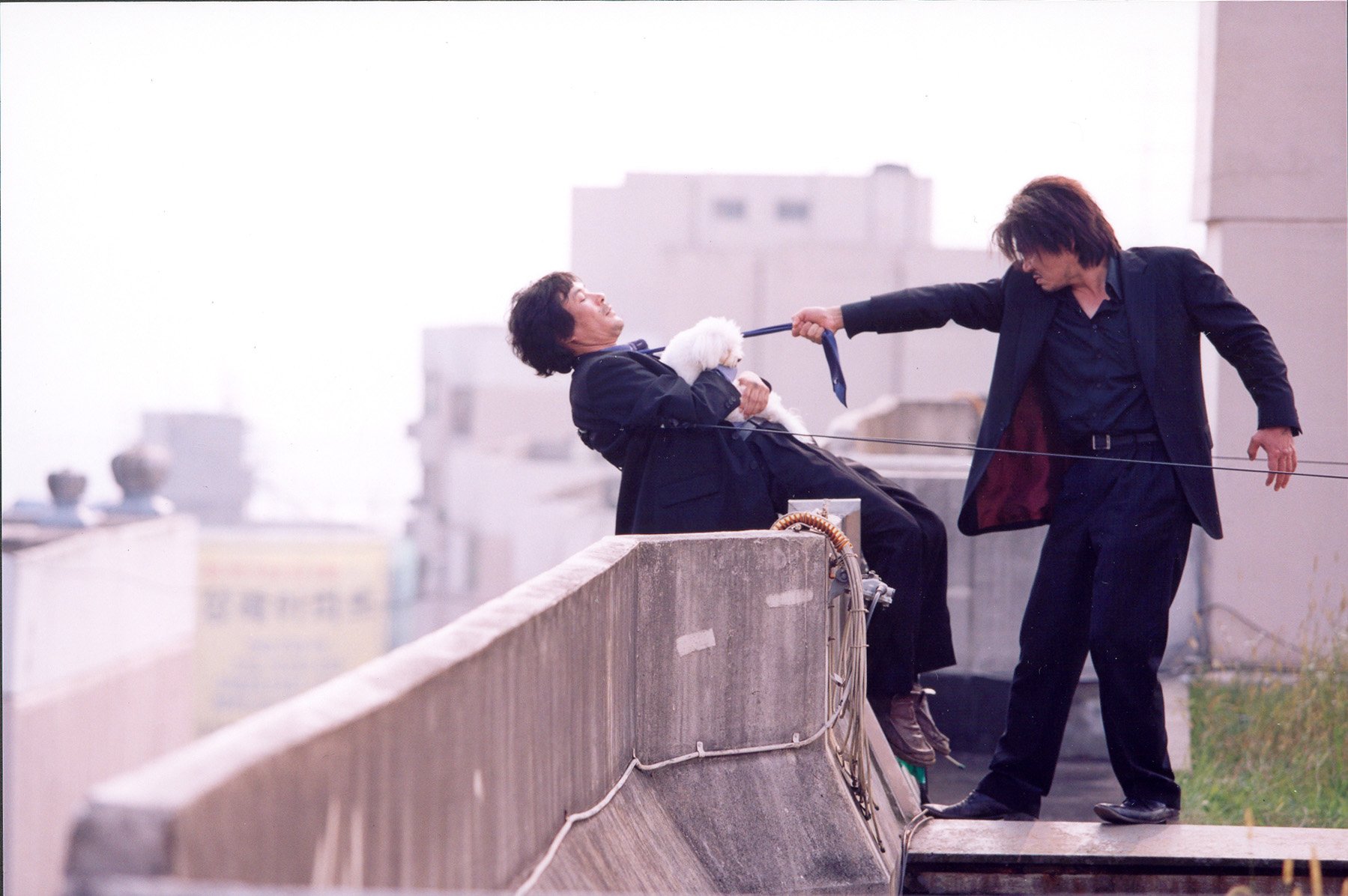

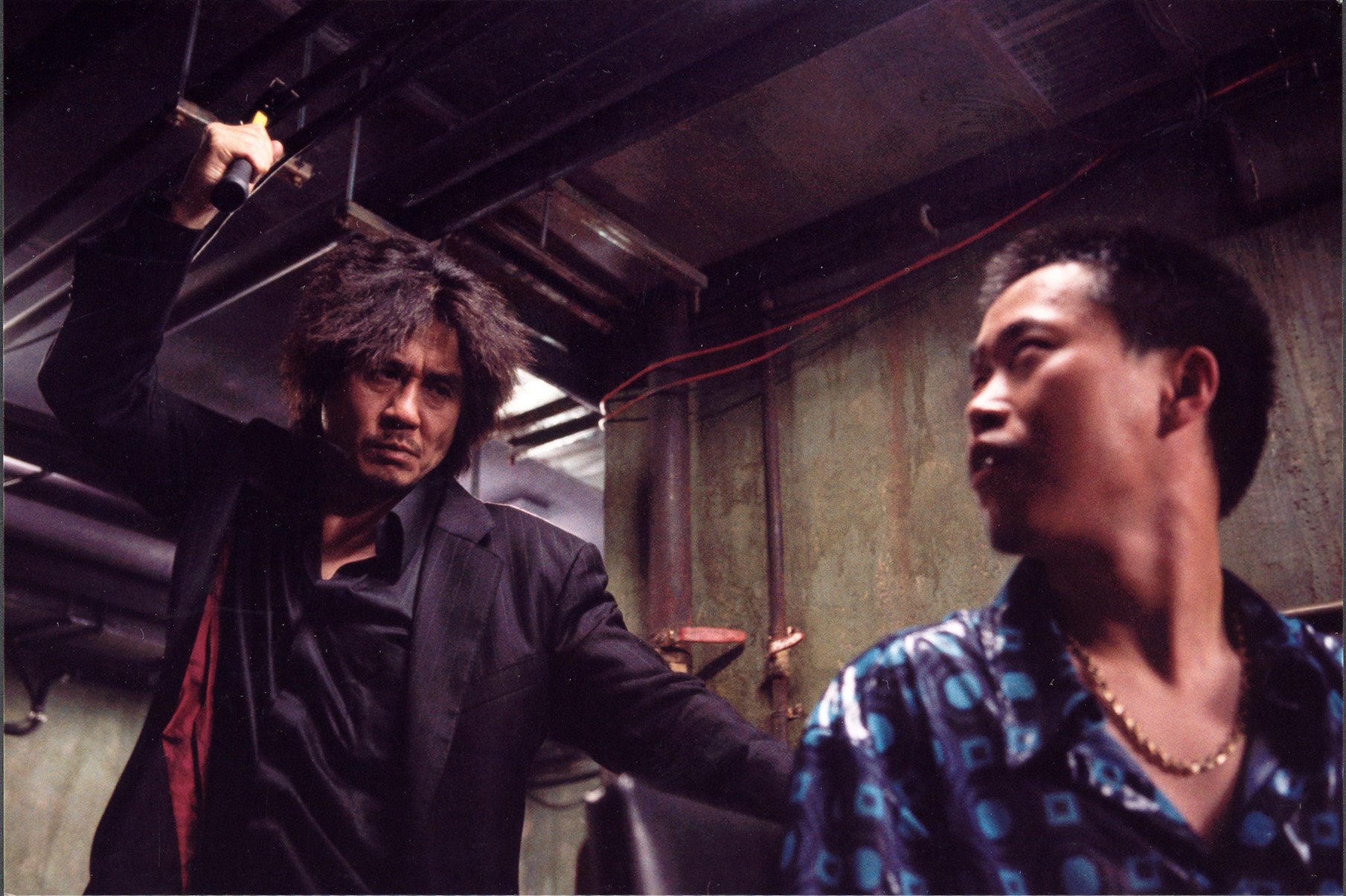

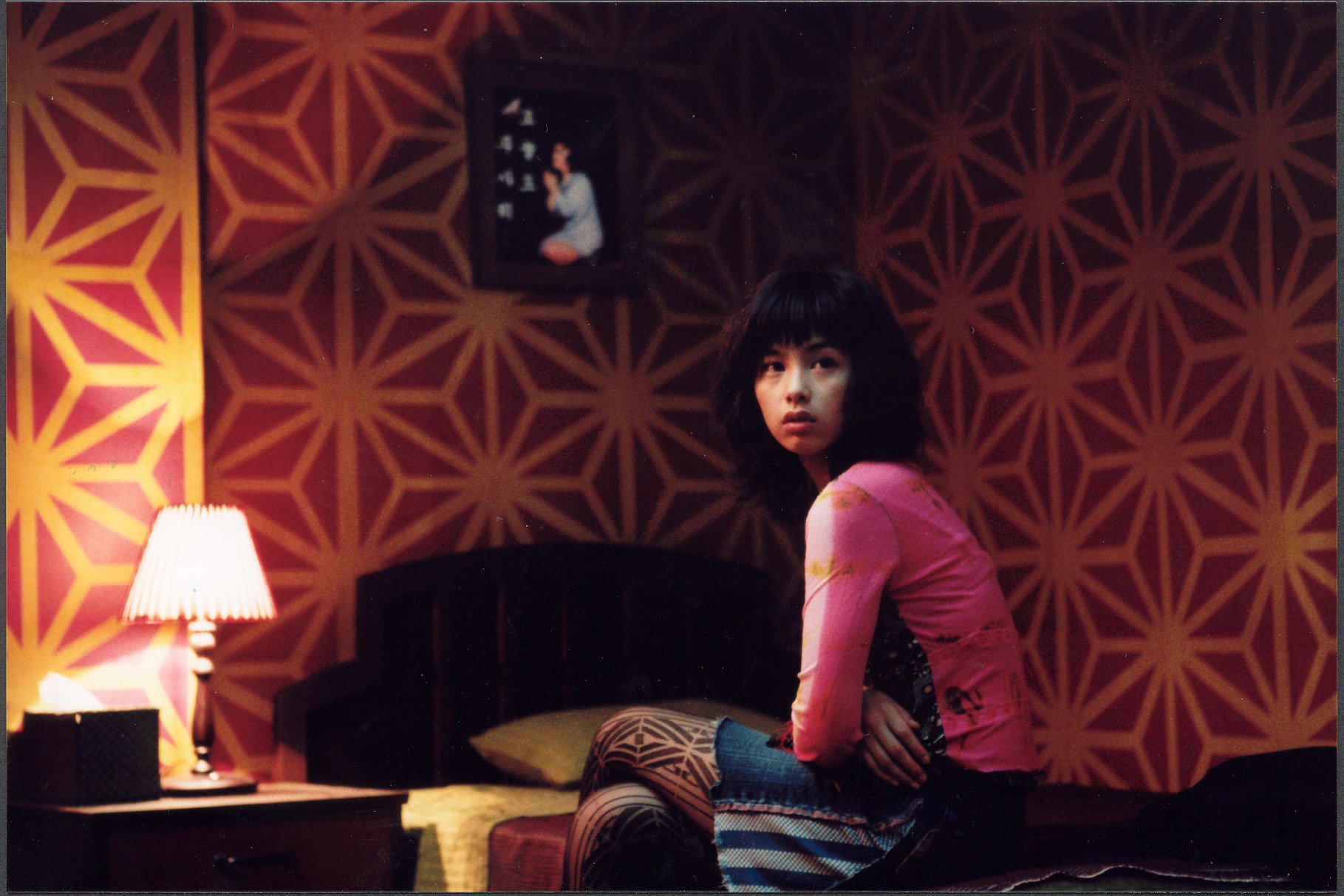

The film is the story of Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), a drunken businessman who, in 1988, wakes up in a locked hotel room, where he is kept without explanation by an unknown assailant. Fifteen long years go by, until suddenly, in 2003, he is released. Oh Dae-su returns to society harbouring an insatiable thirst for revenge (and a ravenous hunger for live octopus), becoming involved with a beautiful young woman, Mi-do, as he tracks down his captor in a haze of hammer-fights and fisticuffs. All the while, the mystery behind his unexplained imprisonment is gradually revealed — in what amounts to, perhaps, Korea’s greatest cinematic feat of all time.

But how exactly did Oldboy become such a titanic hit, and able to effectively launch South Korean cinema into the global mainstream consciousness? The answer, of course, is indelibly tied to the metamorphosis of “Hallyuwood” itself in the years leading up to the turn of the century — the legacy of which is still tangible to this day.

The Hallyu wave and a new Korean film industry

It was in 1988, the same year that Oh Dae-su was arrested in Oldboy, that the seeds for Korea’s nascent filmmaking transformation were sown:

Alongside a new democratic constitution — which granted creative freedoms not permissible in the military dictatorships prior — a screen quota was introduced in 1988 to guarantee that domestically-produced films would receive significant exhibition time alongside foreign imports. The move would provide impetus for home-grown talents like directors Bong, Park and Kim to work towards their own personal breakthroughs in the years that followed, as a new film industry infrastructure was gradually shaped from within.

The Asian financial crisis of 1997 would later prove crucial to the development of New Korean Cinema. With the country in the grips of a major recession, the liberally-minded Kim Dae-jung was elected as President — bringing with him a wave of further economic and social reforms. These included financial incentives designed to ensure the growth of the nation’s film industry, and a doubling-down on the existing screen quota.

The long-term goal was for the country’s native pop culture — including films, music and television — to be exported overseas, much in the same way that electronic goods by Samsung and LG and cars by Hyundai and Kia had been, thus rebranding Korea’s global identity and inspiring economic growth through foreign investments and tourism. But in the short term, Korean cinema was able to flourish: between 1993 and 2002 — the year before Oldboy’s release — Korean films went from returning just 16% of overall attendance figures to finally surpassing those of foreign imports, and thus the era of New Korean Cinema, or ‘Hallyuwood’, was born.

Two icons of the New Korean Cinema

Korean cinema was in increasingly good shape — and so were the minds behind Oldboy. Director Park Chan-wook had already landed a phenomenal hit at home with JSA: Joint Security Area, which, in 2000, broke box office records to become Korea’s highest-grossing film of all-time. The film was also nominated for the Golden Bear at Berlin Film Festival in 2001 — considerably raising the director’s profile in the West — after winning major honours in Korea such as Best Film at the Blue Dragon Awards, and four prizes at the Grand Bell Awards the same year.

Park’s follow-up film, Sympathy For Mr Vengeance, received similar acclaim (and exhibition) via major festivals in Toronto, Tokyo, Philadelphia and, once again, Berlin, as his star continued to rise. The film also refined Park’s visually-striking aesthetics, while establishing themes of bloody vengeance that would become the director’s calling-card in both Oldboy, a year later, and its spiritual sequel, 2005’s Lady Vengeance.

Oldboy’s powerhouse lead Choi Min-sik, of course, was already a well-established Hallyuwood star. He’d been one of the leading men in the 1999 action blockbuster Shiri (alongside the similarly iconic Song Kang-ho, of JSA, Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and Parasite fame) — widely considered one of the foundational films for New Korean Cinema, and the most successful film in South Korean box office history at the time of its release — for which he was awarded Best Actor at the Grand Bell Awards. From there, Choi had picked up acting awards across a slew of Korean film festivals for his roles in films like the 2001 romantic drama Failan, in 2001, and Im Kwon-taek’s 2002 Cannes Best Director-winning Chihwaseon.

The Y2K Asian cinema explosion

While stars like Choi likely helped shape Oldboy’s native success, the bigger story was Oldboy’s international impact. And though director Park’s emergence in European film festivals would have certainly raised the film’s profile, Oldboy’s reach would far surpass that of the film festival crowd.

Oldboy was a notable UK release by the now-defunct distribution label Tartan, as part of their influential Asia Extreme line (much of which is now available on Blu-ray and 4K via Arrow). The cult label were largely responsible for the booming popularity of East Asian horror films around the turn of the century, having brought wildly popular works such as Ring, Audition and Battle Royale to the UK for the first time. But alongside these popular Japanese films — many of which went on to receive big-budget US remakes — arrived like-minded works from places like Hong Kong, Thailand, and, of course, the South Korean industry.

These Korean titles included Kim Jee-woon’s A Tale of Two Sisters, Park’s Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and, of course, Oldboy. The latter would end up being one of the label’s most popular physical releases, and its Western success would eventually inspire a remake itself via Spike Lee in the US a decade later.

A timeless legacy

The prominence of Korean visual media across the globe in recent years offers the most obvious evidence of Oldboy’s enduring legacy, but the subsequent careers of the film’s various cast and crew members are also testament to its lasting significance.

Among his many subsequent global successes — Lady Snowblood, Thirst and the BAFTA-winning The Handmaiden among them — director Park made the jump to Hollywood in 2013 with Stoker, and directed Oscar nominees Florence Pugh and Michael Shannon in his BBC series The Little Drummer Girl in 2018. Choi Min-sik, meanwhile, would appear opposite Scarlett Johansson in Lucy, in what was his 2014 Hollywood debut, while remaining at the forefront of Korean cinema via films such as I Saw The Devil, New World and The Admiral: Roaring Currents. The latter remains the current highest-grossing film of all time in South Korea.

Cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon, meanwhile, has recently become hugely relevant following a long-standing partnership with director Park. He was director of photography for Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho this year, and has now just completed work on the Disney+ Star Wars mini-series Obi-Wan Kenobi, due for release in 2022.

And while films such as Parasite and shows like Squid Game hit major milestones in terms of awards ceremonies and viewing figures, Oldboy ultimately remains the tooth-cracking, corridor-smashing classic that put the whole South Korean filmmaking ascendancy into motion. For that, it retains a unique and untouchable place in Korean cultural history — a masterwork that embodies New Korean Cinema to its core.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4UUGIIZxFU&t=30s