From the suffragettes to second wave feminism and the then-called “women’s lib” movement to the 2017 re-emergence of Tarana Burke’s #MeToo movement, angry women learned well over a hundred years ago an important lesson: if you want to make an impact, travel in packs. When it’s one woman crying foul, she’s accused of being “difficult”, “high maintenance”, “a princess”. But when it’s an army of women bellowing for the same thing, and visibly prepared to fight for it? Then we’re much, much harder to dismiss through these long worn-out sexist dismissals.

In Bev Zalcock’s essential 1998 book Renegade Sisters: Girl Gangs on Film, she defines a girl gang as “three or more female characters working together to resist oppression and fight back against injustice”. Even with a definition that precise, in exploitation cinema alone this means girl gangs manifest in a whole range of different types of movies. For Zalcock, these include (but are certainly not limited to) women in prison films, girl school movies, all-girl biker gang films, and even groups of women vampires (tantalisingly labelled here by Zalcock as “fang gangs”).

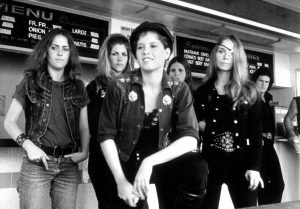

In the perhaps most readily identifiable manifestation of the girl gang film, however, we find bad-girl juvenile delinquency films that typify movies like Jack Hill’s legendary Switchblade Sisters (1975). In their evolution from the Dagger Debs to The Jezebels, under the emerging control of Maggie (Joanne Nail) the latter consciously shun through their new name itself any defining reliance on male counterparts. Embracing The Jezebels label is in itself demonstrates an act of feminist agency, of moving on from a dependence of a dominant, controlling masculine force.

And like so many of their girl gang sisters, The Jezebels have a lot to be angry about. At first, they are just she-thugs and girlfriends, but as the film progresses their fury mobilises and their focus becomes increasingly closer to that of grass roots, fire-in-the-belly activism than just being a group of wild young women out to cause miscellaneous trouble. While not immediately conceived through the lens of the rape-revenge film that was flourishing in North American exploitation cinema during this era in particular, there are perhaps curious intersections that, when considering the centrality of the girl gang to Switchblade Sisters, is worth thinking through further.

This was, after all, the time of grindhouse classics like Henning Schellerup’s 1973 film Black Alley Cats and Robert Kelljan’s 1974 movie Rape Squad (the latter renowned for its hockey mask wearing serial perpetrator the “Jingle Bells Rapist” who looks more than a little like Jason Vorhees as he would appear from Steve Miner’s 1982 film Friday the 13th: Part III onwards). Girl gang rape revenge films have persevered in movies including The Ladies Club (Janet Greek, 1986), Blood Games (Tanya Rosenberg, 1990), Tomboys (Nathan Hill, 2009), Julia (Matthew A. Brown, 2014) and, most recently, Melanie Aitkenhead’s Revenge Ride (2020) starring Pollyanna McIntosh, the latter which combines the all-girl motorcycle gang model with the rape-avenging girl gang one. (As an aside, it’s interesting here how many of these films are directed by women filmmakers; perhaps they should form a gang of their own?).

While there’s far too much else going on in Switchblade Sisters to reduce it purely to a rape-revenge film, certainly those elements are there and the film features two distinct and fascinatingly very different sexual assaults that each, in different ways, propel the narrative (and that’s not even including the sexually sadistic prison warden Mom Smackley in juvie). The first is the most challenging, perhaps, as it blurs the issue of consent well beyond the predominantly black-and-white binary manner that it is usually approached in exploitation movies (and indeed, cinema itself) more broadly. The second sexual assault is much more legible on this front although not as explicit, as one of the Dagger Debs is gang raped by Crabs and his gang in the back of a van.

As different as these scenes are from each other, they ultimately communicate the same thing; it’s a man’s world that these women live in, and for all their tough girl posturing, they are at the mercy of the patriarchy, no matter how much the representatives of that system define themselves as anti-system outsiders. It is here where arguably the most radical and enduring aspect of Switchblade Sisters becomes visible; faced with the reality of what it means to be the downtrodden victims who have had enough, they regroup, reform and reimagine themselves as less a traditional juvenile delinquent girl gang and as something much more exciting; a wild, anarchist feminist activist group.

Where they turn to learn about activism is fascinating. On one hand, the introduction of Muff (Marlene Clark) and her army of Black Maoist feminist radicals can superficially be seen to introduce elements of the then-popular Blaxploitation trope into the mix of which of course Hill was already a master with films like Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974). But both Blaxploitation and rape-revenge were, as Stephanie Dunn wrote in her 2008 book "Baad" Bitches and Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films, already a comfortable fit as "the tough, sexy, avenging black woman personified in Coffy and Foxy Brown emerged during a period that the B-grade rape and revenge films appeared amid the second-wave feminism of the 1970s".

When Maggie turns to Muff and her comrades, she does much more than take things up a notch for her gang sisters as they evolve from the Dagger Debs to The Jezebels. Rather, they radicalise with a fundamentally ideological intent – driven by a history of oppression and a genuine fury to shake things up – that, for Maggie, must necessarily be driven by an intersectional engagement with women whose experience and expertise is beyond their own as white women. Switchblade Sisters is an exploitation film good and proper, make no mistake about it, but that doesn’t mean it lacks an ideological punch to the guts.

Watching that final scene as Maggie explodes with fury, vowing that The Jezebels will return, the threat is palpable. The return keeps happening, not just in film, but in our own world, and it will keep happening until the epidemic proportions of violence, abuse and harassment that women still face every single day isn’t addressed. Across decades, across the boundaries between film and reality, across national borders: as the girl gang film taught us, we are strong when we are unified. And we will not stop. We won’t stop returning.