When one thinks of martial arts cinema, the first figures that typically come to mind are Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan. However, lurking in the depths of many people’s minds is a bald-headed, stern-faced Shaolin monk with a three-section staff in hand. This is, of course, San Te, the hero of The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). Widely recognised throughout world cinema, the film is the first in a trilogy of masterfully directed kung fu flicks among some of the finest in the Shaw Brothers catalogue.

The genius behind The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, and indeed a wealth of other classic kung fu films, is Lau Kar-leung. As a director, actor, and choreographer, it’s hard to overstate just how much of an impact Lau had on the Hong Kong film industry. The late filmmaker came from a prestigious kung fu lineage; his father and teacher, Lau Cham, studied under Lam Sai-wing, himself a student of the legendary martial artist Wong Fei-hung.

Lau’s upbringing dealt him a wealth of knowledge concerning martial arts legends, building the foundation for the righteous characterisation of his protagonists. His insistence that cinematic martial artists should adhere to a strict moral code led Lau to fall out with the hugely influential director Chang Cheh during his time with Chang’s Film Company, a Shaw Brothers subsidiary in Taiwan. The spat saw Lau return to Hong Kong to direct his first feature, the successful The Spiritual Boxer (1975).

At Lau’s side during this period was the young stuntman Gordon Liu. A martial artist first and an actor second, Liu took up kung fu at a young age, secretly studying the hung ga style at Lau Cham’s school. Lau Kar-leung hired Liu to join him in Taiwan in the mid-seventies before luring him back to Hong Kong to star in his second and third features: Challenge of the Masters (1976) and Executioners from Shaolin (1977). With Lau working his magic behind the camera and the enthusiastic young Liu finding his feet as a leading man, all the ingredients were there for a martial arts masterpiece.

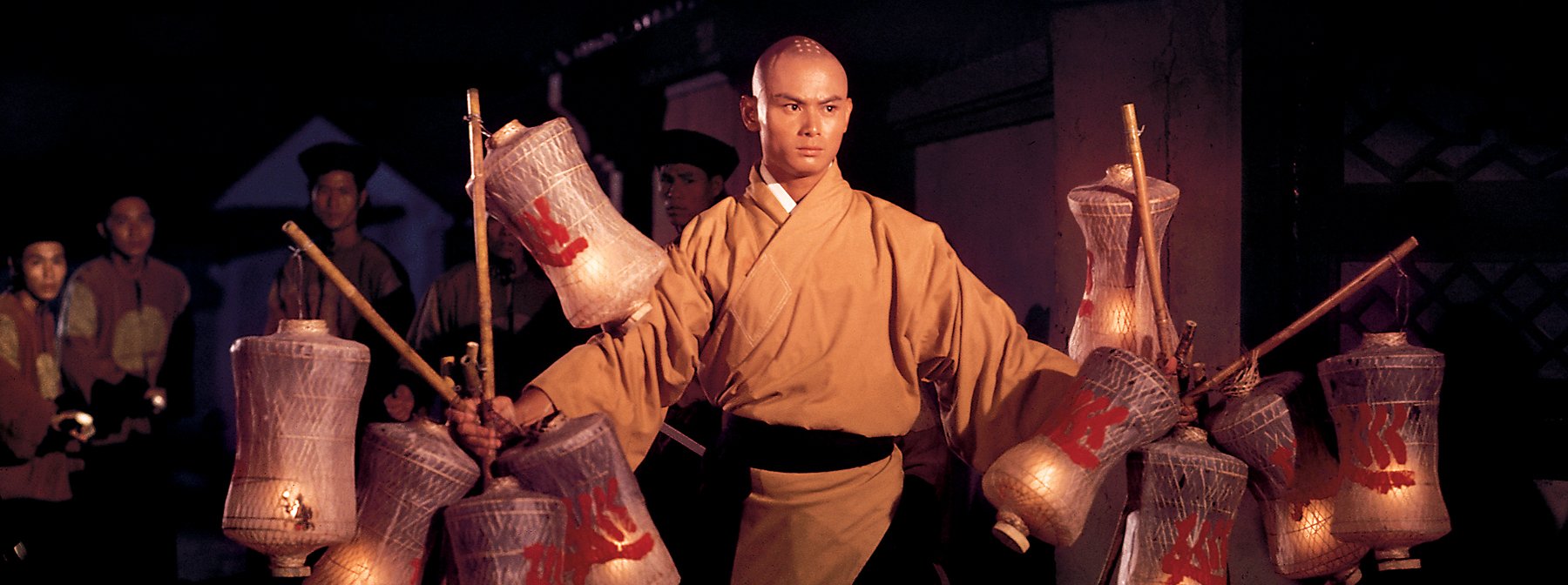

Released in February 1978, The 36th Chamber of Shaolin is a relatively unique film in the broader context of kung fu cinema. The movie starts in familiar territory, as Gordon Liu’s rebellious student, Liu Yu-de, disrupts the rule of oppressive Manchurian invaders. When his covert efforts are uncovered, Liu seeks out the monks of Shaolin Temple, whose kung fu is said to be unbeatable.

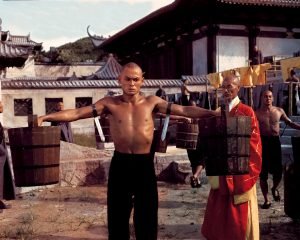

It’s here where the film deviates from the typical revenge narrative, as we spend an extraordinary amount of time on Liu’s training. Adopting the name San Te, taken from the legendary 18th-century Shaolin monk, we follow him through the temple’s thirty-five inventive training chambers, each posing distinct challenges that make for satisfying payoffs later on.

Unlike similar Shaw Brothers flicks, The 36th Chamber is less about the hero quenching their thirst for revenge than about pushing themself beyond their limits to master valuable skills. San Te’s journey through the temple is not without struggle, as the young monk fails time and again on his way to the top. Seeing his drive and determination as he progresses from hapless trainee to chamber master isn’t just satisfying, it’s inspirational.

So iconic is The 36th Chamber of Shaolin that it often overshadows the subsequent two entries in the loosely connected trilogy. Two years after the initial film, Liu starred in Return to the 36th Chamber (1980), this time in the role of Chao Jen-Cheh, a bald conman hired to pose as the fierce San Te by oppressed workers at a fabric dyeing mill. When the listless Chao is found to be a fraud, his guilt drives him to sneak into Shaolin Temple, where he hopes to learn kung fu from the actual San Te.

The sequel marks a significant tonal shift from the first film, as Chao is a far goofier protagonist than the stoic San Te. The role sees Liu flex his comedic muscles, with his blend of impeccable timing and skilful physical comedy rivalling that of Jackie Chan. His exaggerated blows and vacant expressions showcase his acting chops alongside his martial arts prowess.

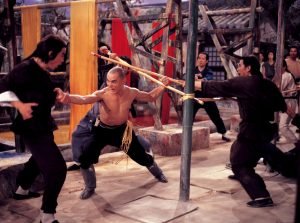

Return serves up a stable diet of action throughout, the choreography of which is nothing short of genius. Chao is forbidden from training in the 36th Chamber, instead tasked with raising scaffolding for temple renovations, which results in him picking up some unorthodox skills. The final confrontation is as exhilarating as it is devilishly clever, with Chao literally tying his enemies in knots.

A tighter, action-heavy follow-up, Return is arguably a more refined film than its predecessor, although it is, admittedly, an entirely different beast.

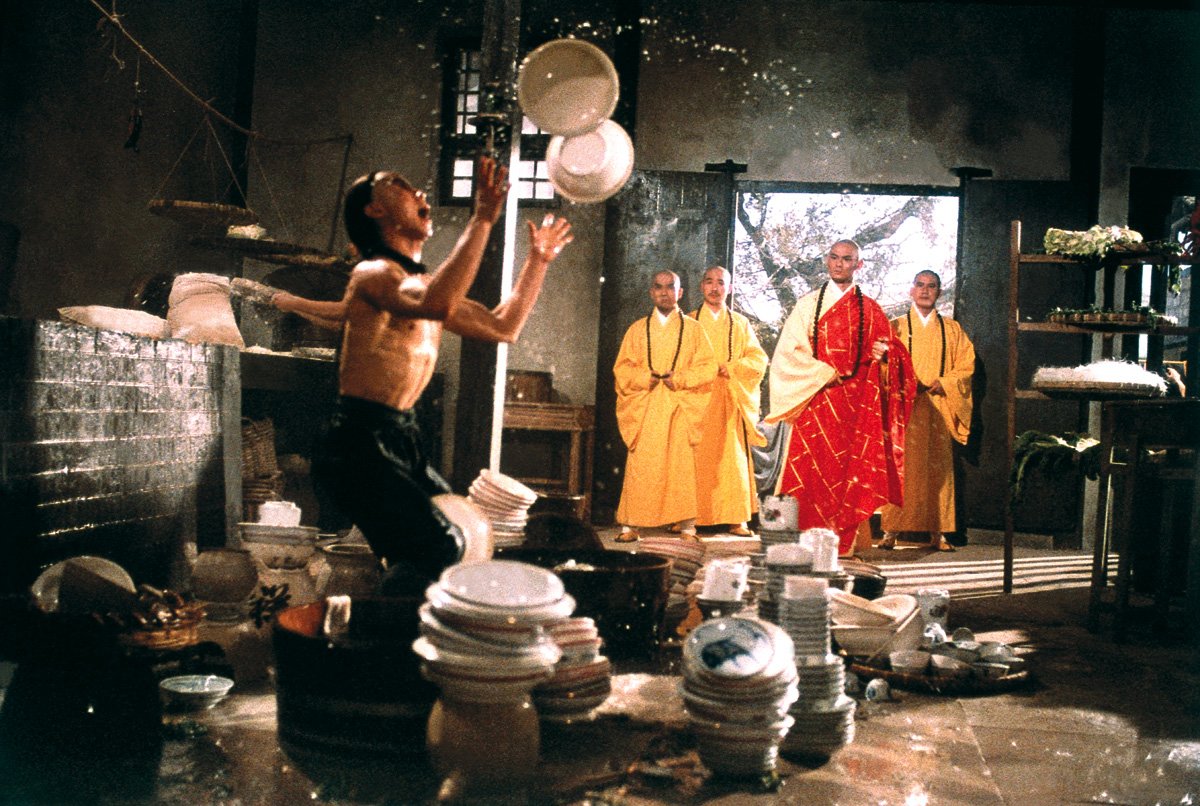

Lau and Liu re-entered the 36th Chamber together one final time in 1985, the same year that Shaw Brothers ceased film production. In Disciples of the 36th Chamber, Liu reprises the role of San Te, playing second fiddle to the troublesome young protagonist, Fong Sai Yuk (Hsiao Hou), whose journey mirrors that of his monk mentor in several ways. A roguish and impulsive student, he can’t help but cause mischief, especially at the expense of his Manchurian overlords.

While both are proficient in kung fu, San Te and Fong could not be more dissimilar as personalities. San Te’s diligence and hard work contrast with Fong’s boredom and laziness, as the young fighter believes himself too good to train in the 36th Chamber. This characterisation does not totally work, as Fong can be an irritating and even unlikeable hero. Yet, it does mark an interesting shift in Lau’s narrative approach, as he replaces the wise and focused protagonist with a young rapscallion.

Disciples still features some stellar martial arts choreography; one duel between San Te and Fong involving benches is positively mesmerising. Moreover, the vibrant and chaotic finale is ambitious in scale, filled with several complicated set pieces. It’s easy to take for granted the gracious flow of Lau’s action scenes, such is the skill with which they are executed.

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin was a hit for Shaw Brothers and, perhaps more significantly, marked an international success for the studio, famously releasing in the USA with the title “Shaolin Master Killer”. For many, Gordon Liu’s San Te is the unlikely face of martial arts cinema worldwide. Director Lau Kar-leung would go on to direct into his early seventies, yet his work on the 36th Chamber trilogy remains some of his finest. The timelessness of the original film, the comedic flair of the sequels, and the thrilling action all make the trilogy essential viewing.