Woodman, spare that tree!

Touch not a single bough!

In youth it sheltered me,

And I’ll protect it now.

― George Pope Morris, “Woodman, Spare that Tree!” (1837)

Imagine an untouched forest planet. Nothing human, just the flora and fauna seeded by a fallen habitat from space; its surviving gardener, Dewey the drone tending a vast green world with hardly a reminder of humanity… not even the robot in man’s image. This is just one variable in which Doug Trumbull’s 1972 debut Silent Running [1] leaves us with; a film that concerns itself not with the grander ideas of space travel but more with what we have discarded. Ultimately a film about conservation, this eco-sci-fi not only delivered a powerful message 50 years ago but is now more relevant today than ever before.

Another Eden

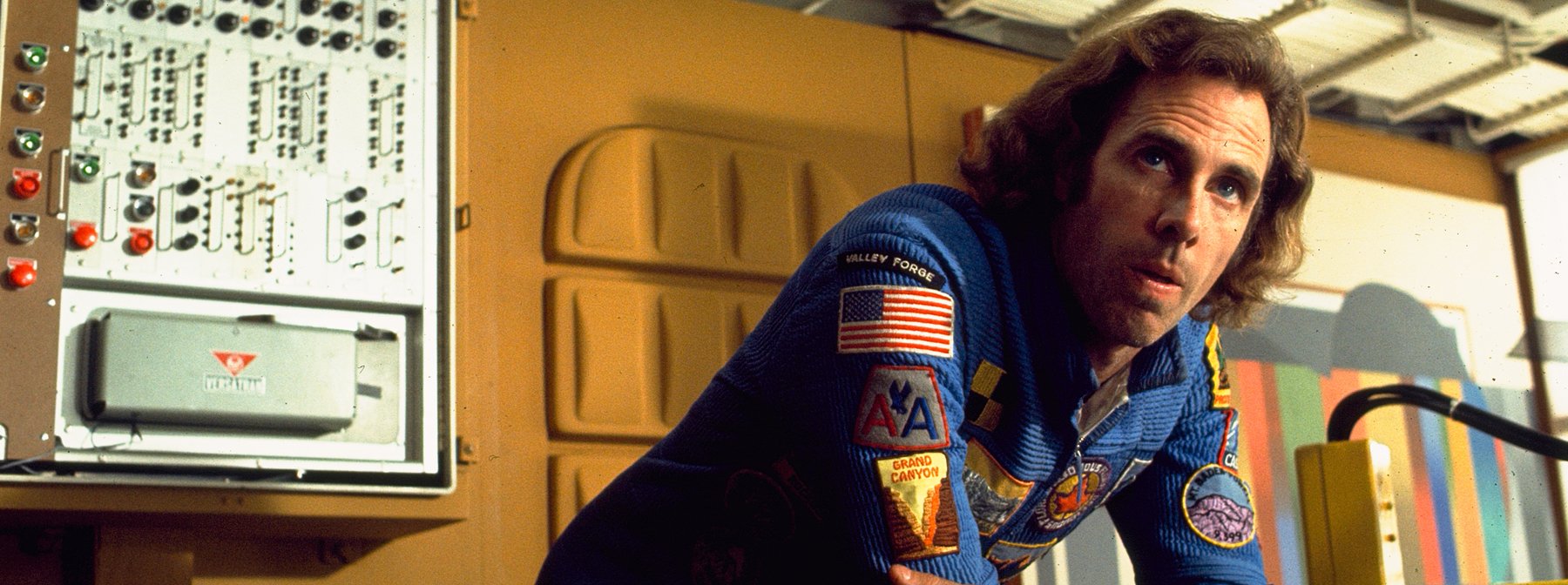

No starfield prologue here. Disarmed from the offset, the camera ― married to Peter Schickele’s melodic score [2] ― glides over a dew-laden environment from flower to insect to amphibian and mammal before revealing a hint of artificiality. A geodesic dome triangulates the stars as we are introduced to Freeman Lowell played by Bruce Dern. Under Saturn’s looming presence we are aboard the American Airlines Space Freighter christened ‘Valley Forge’ in which a crew of four men work at preserving the last of Earth’s plants and wildlife. A mile in length, the spaceship is a practical design made up of girders, fuel pods, nodules and the geo-domes that house rare samples of life; all that remains of our deforested planet. Committed to the cause, Lowell is a man engaged with his work and surroundings, while the rest of the (bored) crew race buggies around the ship’s vast and empty spaces. In complete disregard for what they have tended to, the crew receive an order to abandon and destroy the project. The message, no different in tone to a war announcement, highlights the insanity of the situation ― the detonation of each habitat by a nuclear bomb ― and is exemplified all the more by a gleeful detachment and disdain for their work as Lowell quietly contemplates the reality of the situation… “There is no more beauty, and there’s no more imagination. And there are no frontiers left to conquer.” Fuck conservation. Lowell’s universe displays capitalism at its most extreme.

In looking at the history of conservation the movement can be traced back centuries; as far back as the 17th when timbre resources in England had become depleted leading to landowner (and gardener) John Evelyn (1620-1706) responding in his influential work ― Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty’s Dominions ― that was eventually published in 1664. Over 170 years later in America poet George Pope Morris (1802-1864) published “Woodman, Spare that Tree!” in 1837; a romantic poem [3] centred on urging a lumberjack to avoid felling an oak tree of sentimental value. It is in the words of Lowell’s mantra ― his ‘Conservation Pledge’ ― that Morris’ sentiments are echoed across space; “I give my pledge as an American to save and faithfully to defend from waste the natural resources of my country ― its soil and minerals, its forests, waters and wildlife.”

From a U.S. perspective ― especially catapulted into space ― the film still manages to claw onto these beliefs that still ‘planted’ themselves in America. Such inspired works of the 19th century focussed on the inherent value of nature; often philosophised by the likes of American transcendentalist and author Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) who, while living close to it, was interested in man’s relationship with nature, eventually publishing his experiences in his book Walden (1854). The inherent value of nature was crucial within the American conservation movement from this period onwards; both conservationists and preservationists were involved in fierce debates during what became known as the Progressive Era from the 1890s to the late 1910s. Motivated by the waste and destruction of the forests through logging and hunting, the conservationists happened to be led by future President, Theodore Roosevelt ― who placed such issues high on the national agenda establishing the United States Forest Service ― along with anthropologist George Bird Grinnell. It was the preservationists, led by the influential John Muir (aka ‘John of the Mountains’), who argued that the conservation policies were not enough, as they still tended to focus on the natural world and how it could benefit the economy.

Flower power

In 1970 ― despite his warmongering and deceit ― president Richard Nixon helped to create the Environmental Protection Agency and became a major part of an environmental re-emergence; debates over public lands of which led to a decline of liberalism and a lean towards the rise in modern environmentalism that seemed to fit with remnants of the counterculture movement left over from the previous decade. Most would believe this was a positive drive, but only contradicted Nixon’s scandalous activity and carpet-bombing of Vietnam’s beautiful landscape. These policies only remind us further of the contrast between the optimism of the moon landings and the fallout and turmoil of the ’60s ― Lowell’s frustrations and reaction to his crew following orders reflecting the heel turn of politics during this period. Post-Watergate, the conservative attitudes of the time began to build new organizational networks and deploy fresh strategies that affirmed property and extraction rights. Now, anyone could continue to take from the land without federal government control and therefore were in direct assault and at the expense of conservation.

Silent Running is the perfect depiction of such historical events. Far from a poor man’s 2001, Trumbull aimed “more for the heart than the head” [4] every effort made to lean more towards the eco and humanist themes. Keen to capture the imagination of a newly politicised generation he aborted his ‘alien contact’ premise and, instead, embraced anti-war sentiments involving the critique of nuclear arms and the destruction of entire ecosystems. “Both films (2001 and Silent Running) explore the capacity of human potential. 2001 looks up, searching for a higher-power inhabiting the heavens, be it divine or extraterrestrial, while for Trumbull ― in keeping with the film’s ecophilosophy ― it’s only by looking within ourselves can we truly expect to evolve.” [5] It may be set in the cosmos but is certainly a microcosm of humanity’s ability to destroy. Lowell feels less an inheritor of the first men on the moon and more an inheritor of this lineage of conservationists ― ‘flower power’ and hippy bullshit perhaps, but a marker for the best of humanity.

In light of this, to prove our worth we must face the consequences of our actions… and the impact of nature is a destructive reminder. Some of the most iconic works of science fiction have tapped into this, such as Ishirō Honda’s original Godzilla (1954) ― an obvious metaphor for the nuclear destruction rained down on Japan’s cities ― and, in operatic contrast, Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) in which an entire universe was built around the central themes of man’s ultimate power (and reconnection) with natural resources. Herbert’s threat ‘grows’ over centuries; it evolves, planted in minds as much as Arakis’ ecology. Although the ecological themes are not so literary as the likes of John Wyndham and Jack Finney’s plant-based invasion of Triffids and Body Snatchers ― or as surreal and dreamlike as René Laloux’s La Planète Sauvage (aka Fantastic Planet, 1973) ― it is in the downplay of apocalyptic events that Silent Running shares their reproach.

These quiet influences and Trumbull’s lo-fi aesthetic can also be seen in many films that followed including (more hippies in space) via John Carpenter’s debut feature Dark Star (1974) [6], Richard Fleischer’s Soylent Green (1973), Justus E. McQueen’s A Boy and His Dog (1975), Duncan Jones’ Moon (2009), and, more recently, Zeek Earl and Chris Caldwell’s Prospect (2018), Hugo Lilja and Pella Kågerman’s Aniara (2028), and Kristina Buozyte and Bruno Samper’s immersive biopunk fable Vesper (2022). Next year’s Scavenger’s Reign (2023) based on the original 2016 short also returns to familiar (albeit a tad more surreal) territory judging by the trailer.

Silent ending

Science fiction often concerns itself with man’s ability to colonise or conquer. Space may be the final frontier but it is amongst the hard edges of technology and the discovery of alien life that other prevalent stories seem left behind. The genre thrives on the zeitgeist… feeds off it; often projecting whatever social issues of the time are being discussed or (in some instances) ignored. As an ecological science fiction movie, Silent Running presents perhaps the most prevalent argument of all about conservation and preservation; a blatant reminder of the current ‘climate’ surrounding the repercussions of global warming and climate change. But, on a human level, it also presents how far we are willing to go for our beliefs; the selfless actions of an individual vs. the selfishness of group thinking and megacorporations.

How far does Lowell go? The Valley Forge is his Yellowstone ― a beacon of hope and preservation ― so when news arrives that the utopian project is to be abandoned, in an extreme act of violence he murders his crewmembers in an effort to prolong Earth’s last surviving natural habitats. Alone in the void, he grapples with the consequences of his own actions, with nothing but the company of robot drones. It is at this point ― as one of most human of sci-fi tales ― the film’s charm and tenderness are fully revealed as he is carefully ‘fixed’ by the remaining drones he has humanised by nicknaming them Huey, Dewey, and Louie. At that moment Lowell realises there is nothing left but to tend to the surviving habitat while retaining what remains of his sanity… and soul. He becomes so lost he no longer notices the lack of sun (the science of the film questionable) when he fails to diagnose the “ills of the forest”, having become so distracted that “he just can’t see the wood for the trees.” [7]

All of this presents an alarming realisation of man’s extinction and what we leave behind ― the harmony of nature and technology and a possible ‘engineered’ wilderness. Thematically it remains an emotionally complex story that not only deals with the responsibility of saving ‘life’ but also, on a very human level, guilt and loneliness. In terms of production, what makes this ‘king of lo-fi sci-fi’ even more unique in its vision of the future is the film’s economic [8] approach that only bolsters the narrative and central themes further… storytelling that is left to grow amongst the stars.

After his pioneering work on 2001:Space Odyssey (1968), the late visual effects artist Douglas Trumbull (1942-2022) was one of many to eventually ‘jump ship’ working with Stanley Kubrick due to low morale and bitter feelings towards the director. Moving on, Trumbull quickly invested his talents into Silent Running. He would go on to create the visual effects for his Oscar-nominated UFOs in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), become a major hand in bringing the world of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) to life, and, in a nod back to his 2001 roots, create the ‘universe’ sequence from Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011).

Schickele’s whimsical and somewhat optimistic folk score also shows off singer Joan Baez’s beautiful voice. She laments and rejoices throughout reminding us of the “harvest” and other key themes throughout… “Running silent in my sleep.”

“Woodman, Spare that Tree!” was first published in the January 17th issue of the Mirror in 1837 under the title “The Oak” and was that year set to music by Henry Russell before being reprinted under its more common title in 1853.

Mark Kermode, Silent Running (BFI Film Classics), London, British Film Institute, (2014), p.17.

- Brian Quinn, “Silent Running remains a tender riposte to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001”, Little White Lies, London, TCOLondon Publishing, (2020), (accessed 21st November 2022).

The history of Dark Star overlaps slightly with Silent Running’s production, built on Carpenter’s original short film that was produced from 1970 to 1972.

M. Kermode, p.73.

On a $ 1 million budget Trumbull’s limitations saw the director take full advantage of existing interiors utilising a decommissioned Navy aircraft carrier – the USS Valley Forge in which it took its name – while also saving time (and money) in post-production with most of the special effects built on set through ground-breaking model work and innovative front projection that further set the precedence for George Lucas’ Star Wars five years later. It is no surprise that as the son of a commercial artist and engineer and having worked on pre-visualisation for the Apollo programme for NASA that Trumbull put his ‘realism’ to the test.