Japan’s no stranger to tragedy. It was only ten years ago the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, shocked the world as one of the most costly and deadly natural disasters in modern history. Partnered with an economic crisis that has lingered on ever since the bubble economy burst around 1990, it makes sense why this year’s Tokyo Olympics were referred to as the “recovery Olympics”. But despite these incidents, and speaking in broad and general terms, it could be argued that the kids of Japan today have it easier than most.

Here are the facts: Japan’s homicide rate remains one of the lowest in the world as of 2019, at just 0.3 per 100,000 members of the population. In 2020, the country had the fourth-highest employment rate on a global scale and the second-highest job security behind only Switzerland. The country hasn’t been involved in any major wars since World War Two. And citizens can expect to live to over 84 years old, since the nation maintains the second-highest life expectancy in the world. It’s no wonder, then, that Japan’s children are reportedly the happiest in the world today.

But if you wind back the clocks, it becomes evident how far the country has come in the past half-century. Because in the decades since the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, Japan has been the site of some of the most dynamic student protest movements, the most vibrant youth cultures, and, of course, some of the most captivating strands of juvenile delinquency cinema in the world.

With the Arrow release of Sailor Suit and Machine Gun — only a few short months after the re-release of kids-gone-wild cult classic Battle Royale — we take a broad (but by no means comprehensive) look at the myriad strands of rebellious cinema to emerge from Japan since the post-war era, and the socio-political roots that fuelled them. It’s clear that the youth have had plenty to rally against over the years.

The ‘50s

Youth delinquency was a global issue in the post-war years, and one reflected in cinema everywhere from Rebel Without a Cause to François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. Japan, which had endured destruction and socio-economic hardship during the war and its aftermath, before being thrown into an intense restructuring process under the wardship of the United States, was no different.

Disillusioned youths are the crux of the ‘50s ‘Sun Tribe’ films, which featured young men and women indulging in sex, violence and antisocial behaviour. Examples include Takumi Furukawa’s Season of the Sun, about a boxer who gets his girlfriend pregnant, Kon Ichikawa’s Punishment Room, about a college student who rapes a woman, and, most controversial of all, Ko Nakahira’s Crazed Fruit (all 1956). The latter featured sex scenes between juveniles, and eventually became the target of a moral panic over the film’s perceived corrupting influence.

The ‘60s

The ‘60s gave rise to The Japanese New Wave — a group of emerging filmmakers keen to experiment with style and form while engaging with the thriving social movements that had carried over from the late ‘50s.

Among the most notable of these were the Anpo protests of 1959 and 1960 — a massive, student-led retaliation to a proposed revision of the Anpo Treaty, which would ensure that America could retain a military presence in Japan as the Cold War was waged with Japan’s communist neighbours. Tensions reached a peak in June 1960, when hundreds of thousands of protestors stormed Japan’s National Diet building — with violent retaliation from police resulting in the death of Tokyo University student Michiko Kanba. The protest movement ultimately failed in its attempts to stop the treaty revision — a significant spiritual blow to those who had taken part.

Meanwhile, the widely televised 1960 assassination of Inejirō Asanuma, chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, by a sword-wielding 17-year-old who referred to himself as “Japan’s Hitler”, and later the Zama and Shibuya shootings in 1965, gave the impression that violent crimes committed by young people were becoming more prominent in Japanese society.

The ‘60s would thus be marked by a prevalence of despondent youth films in Japan. Yoshida Kiju (director of 1969 masterpiece Eros + Massacre)’s debut Good-for-Nothing (1960), for example, concerns the petty crimes committed by students as an antidote to their boredom. Fellow Shochiku director Nagisa Oshima (Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence) would deliver the nihilistic Cruel Story of Youth the same year, utilising handheld camerawork in a story about a pair of two adolescent criminals, while Night and Fog in Japan offered a confrontational look at the decline of a student socialist movement in Japan.

The ‘70s

The ‘60s would be marked by rapid economic growth in Japan, with education and income levels rising dramatically as mass urbanisation and industrialisation also took place across the country. By 1967, nearly 90% of the country identified as middle class, as stability was favoured over ideas of violent revolution.

But with sexual liberation and civil rights movements highly visible in the West, the decade also saw a rise in Japanese feminism. Oshima’s 1969 film Diary of a Shinjuku Thief would dive deep into themes of sexual liberation and teen rebellion, while political pink films such as 1971’s Gushing Prayer, which portrayed child prostitution and group sex as a form of liberation, indicated the continued experimentation with the youth delinquency genre. Kaneto Shindo (Onibaba; Kuroneko)’s Live Today, Die Tomorrow! (1970) — also known as Naked Nineteen Year-Old — meanwhile, took inspiration from the spree killings of 19-year-old Norio Nagayama in 1968, which left four people dead.

The decade also saw major studios like Nikkatsu notably lean into more violent or titillating cinema, such as with the Stray Cat Rock series, as the prominence of adult theatres and home televisions transformed the industry. Not every studio was as successful as Nikkatsu and Toei (home of Kinji Fukasaku’s brutal Battles Without Honor and Humanity series) in navigating the changing tides. Daiei, whose works included the Gamera, Daimajin, Yokai Monsters and Zatoichi films, notably went bankrupt in 1971. In 2002, the studio would be bought by Kadokawa Pictures — the production house that had emerged in the late ‘70s and ‘80s through the gap Daiei had left in the market.

The ‘80s

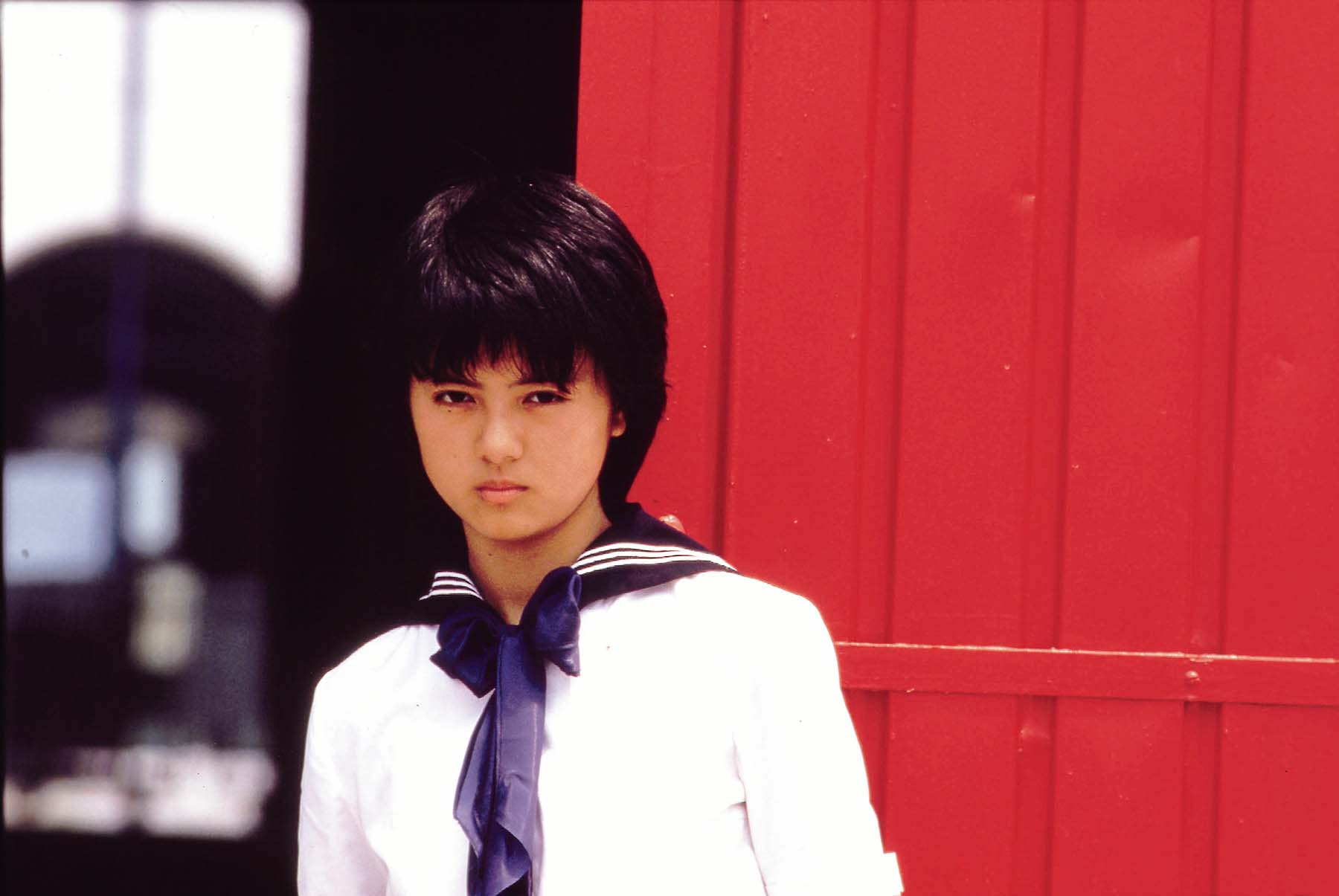

Sailor Suit and Machine Gun was one of the first films from producer Haruki Kadokawa to target teens and young adults, and thanks to its satirisation of popular ‘70s yakuza films, an identifiable lead, and a rousing City Pop soundtrack, it remains a vital text in Japan for a generation of female viewers. Lead character Izumi Hoshi, portrayed by one of the era’s leading idols in Hiroko Yakushimaru, would play a rebellious orphan who drops out of school to lead a struggling yakuza gang. The film became a pop culture phenomenon, with a climactic scene of Izumi wielding a machine gun mimicked widely in playgrounds across Japan.

The late ‘70s also saw Japan suffer economic hardships in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis, giving rise to a new spate of counter-culture movements. The documentary Godspeed You Black Emperor! (1976) had captured the rise of a young Japanese motorcycle gang and their clashes with the law — foreshadowing a spate of ‘80s film centred upon punk, biker gangs and rebellion. Examples include the 1988 cyberpunk classic Akira, as well as Nobohiko Obayashi (Hausu)’s 1986 film His Motorbike, Her Island — the rebel biker romance that introduced renegade icon Riki Takeuchi (Dead or Alive; Battle Royale II) to the world.

Most significant, though, was the “punk” cinema of Sogo Ishii, who directed frenetic, guerilla works like Panic High School, Crazy Thunder Road and cyberpunk prototype Burst City during the same period. The latter film offered a vivid dystopian vision of Japan as an industrial wasteland, collapsed in the wake of an over-zealous technological revolution — a prediction he would get half-right when the economic bubble burst at the end of the decade.

The ‘90s

The collapse of the bubble economy affected the generation growing up in the ‘90s dramatically. Employment rates for universities plummeted to just 66% by 1998. Bullying became rife in Japan’s deeply competitive schools. And teen violence was brought out into the streets in devastating crime cases such as the 1997 Kobe Child Murders and the 2000 Hiroshima bus hijacking. International news media blamed Japan’s singular focus on industry as the cause for social turmoil among the youth, arguing that workplace performance and school achievement had taken precedence over family life and play.

This widespread anxiety was captured with a wave of exciting films about disenfranchised loners and teenagers gone wild. Takeshi Kitano’s Kids Return followed a pair of high school dropouts searching for meaning via the yakuza and boxing. Takashi Miike’s Fudoh: The New Generation depicted a violent yakuza gang based out of high school, and led by uniformed students. Sion Sono’s Suicide Club opened with the mass suicide of an entire class of teenagers — in what remains a definitive scene of the J-Horror movement. And Toshiaki Toyoda’s Blue Spring found a boys school dominated by rooftop death games, and yakuza recruiting new members just outside the school gates.

None would be more significant than Fukasaku’s Battle Royale. The director, who had witnessed the destruction of his own nation during World War Two while working in a munitions factory, understood the parallels between his own generation and that of the late ‘90s, and sought to capture those anxieties. The film remains one of the most notorious ever to emerge from Japan: a Y2K Lord of the Flies where the children must fight until only one remains alive.