In Western horror, two things are generally considered to be off-limits; animals and children. While child death – whether it be infanticide or otherwise – is the backbone of many a beloved horror from the Western world, from Don’t Look Now to Hereditary, the act of killing a child, or the presence of a dead one, remains somewhat taboo. The same cannot necessarily be said for the media of Japan, with Japanese children in horror getting far closer to – and often intimately acquainted – with danger and death on a much more frequent scale than their American counterparts. Many of the classic horror films from the era known as the ‘J-horror boom’ deal with the death of a child, with perhaps the most emotional of them all being Hideo Nakata’s 2002 Dark Water.

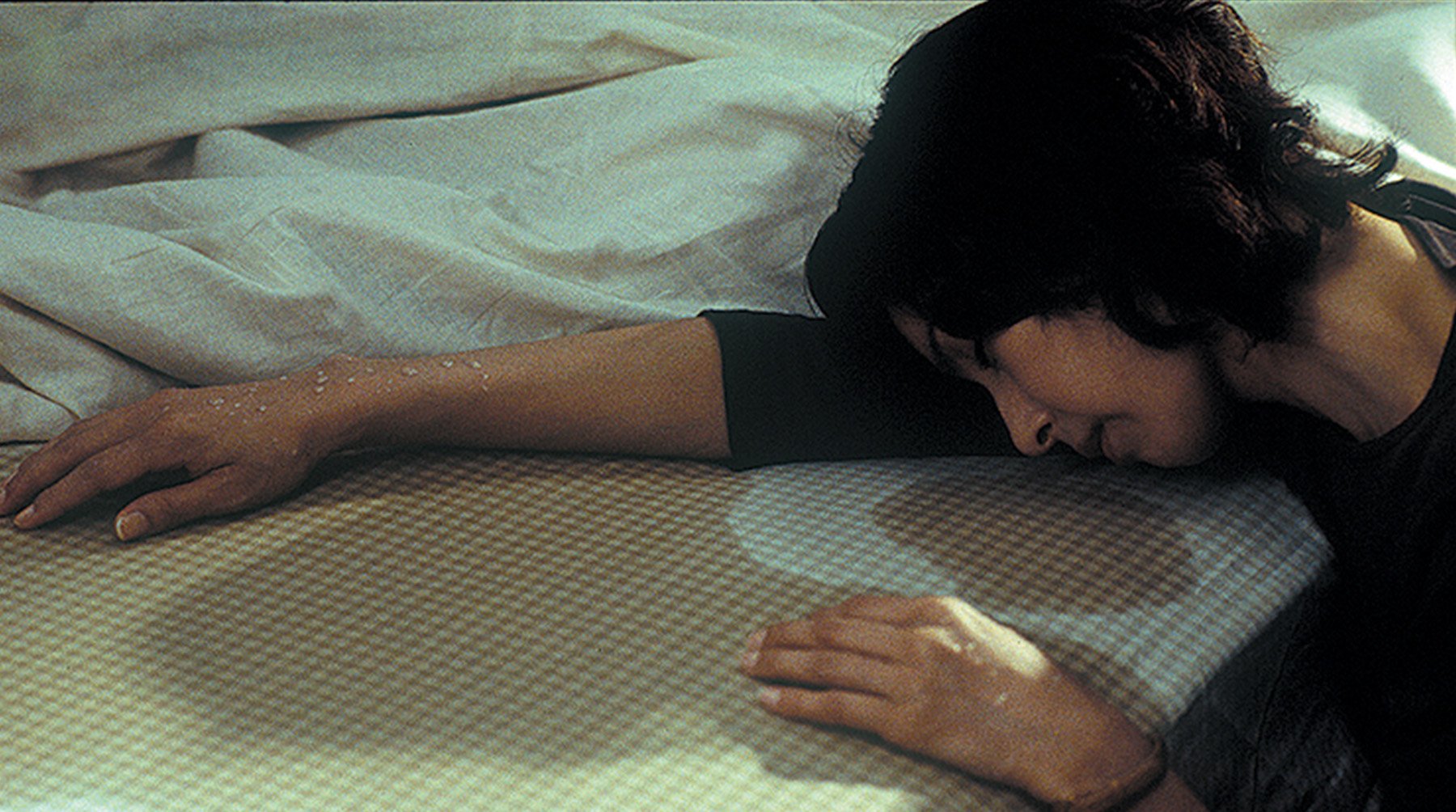

Following the success of 1998’s Ring, Nakata returned to the arena of supernatural horror with a classic, Gothic-tinged ghost story that follows single mother Yoshimi (Hitomi Kuroki) who, in the midst of a bitter divorce, moves herself and her young daughter Ikuko (Rio Kanno) to a run-down apartment building. Creeping damp and constant rain imbue the apartment with a sinister melancholy, as Yoshimi and Ikuko are haunted by the restless spirit of Mitsuko Kawai, a neglected little girl who accidentally drowned in the building’s water tank. Across Dark Water’s patiently paced runtime, we see three children ravaged by cycles of neglect and a manifestation – both literal and spectral – of children’s pain. Much has been written of the role of the mother in horror, but what of the children they leave behind?

The specter of ravaged childhood looms over modern Japan, and while the expected platitudes of the magic of birth are of course socially common, the subject also brings to many a sense of cultural anxiety, particularly when it comes to discussions of Japan’s falling birth rate. In 2002, Dark Water’s release year, Japan’s fertility rate dropped to an all-time low of 1.32. The uncertainty surrounding increasingly aged population with decreasing numbers of babies to balance this top-heavy society may explain why the loss or destruction of a child weighs so heavily upon the Japanese horror landscape. And while there is immense pressure on women to procreate, it could be argued that motherhood is less and less of an attractive prospect for many Japanese women. While advancements in gender equality have seen a rise in work-related opportunities for women, the traditional patriarchal nature of Japanese culture still sees women expected to handle the bulk of the ‘second shift’, shouldering hours of cooking, cleaning and childcare after a full working day. Dark Water’s Yoshimi is a perfect representation of this struggle – fighting for a good life for both herself and Ikuko, whilst also juggling a career she is passionate about and an ex-husband determined to use the misogynistic warfare of ‘madness and hysteria’ to deem her an unfit mother.

Furthermore, the idea of motherhood as malevolence is prominent throughout Dark Water, even from its title alone (Nakata’s most infamous enfant terrible, Ring’s Sadako Yamamura, is herself born from an unholy union between woman and sea.) Across cultures, water is traditionally a symbol of femininity, and furthermore, of motherhood, as every human is born from the dark and salty amniotic brine of the womb. But water does not always play the role of the benevolent, life-giving resource. In Japan especially, water plays a key role in culture, religion and mythology, and not always a good one – and from the humid, suffocating rainy season to frequent typhoons and tsunamis, water is a continual threat to the lives and well-being of Japanese people. In Shinto mythology, stagnant or unmoving water (such as the tank that Mitsuko drowns in) represents an state of ‘kegare’, roughly translated as uncleanliness or defilement. Interestingly, childbirth is also considered an example of kegare, meaning that children and new mothers are considered impure beings for 21 days after birth. Water as negative energy runs rampant throughout Dark Water, with the entire movie stylistically saturated in damp desolation of moody blue hues and sallow yellows. The watery gloom is present even in places that should be bright, colorful havens for children. When Ikuko joins her classmates in kindergarten, their stark blue uniforms hardly make us think of a safe, warm and supportive atmosphere. For the ravaged children of Dark Water, water brings nothing but sorrow and anxiety – and so does motherhood. Mitsuko’s spirit is turned malicious by the water, by her mother, and although Yoshimi tries her best to break the cycle of abandonment perpetuated by her own mother, an utterly heartbreaking finale that sees little Ikuko become the one who is abandoned, left drenched in pain at the loss of her mother.

In general, Japan is a safe country for children, thanks in part to the country’s collectivistic attitude towards respect and responsibility for others, but the years leading up to Dark Water (and various other J-horror classics) had seen numerous horrific crimes across Japan in which children had been a prime target. These included the unspeakable torture and murder of high-schooler Junko Furuta, the heinous crimes of the so-called ‘Otaku Murderer’ which culminated in 1989, the Kobe child murders of 1997, the Osaka school massacre of 2001 and the Setagaya family murder of 2000, which saw the brutal killings of an eight and six year old remain unsolved to this day. Infanticide hung heavy in the cultural zeitgeist leading up to and surrounding the J-horror boom, evident by the increased levels of child death in the horror of this time.

It makes perfect sense then that Ikuko and Sadako are far from the only children in Japanese horror who suffer at the hands of the adults tasked with protecting them. Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-On series subverts the trope of a female ghost child by positing little Toshio Saeki alongside his mother Kayako as the central antagonists throughout the series. Toshio’s violent death at the hands of his father Takeo stems (in the original timeline) from paranoia that the boy had a different father. Similarly, Shimizu’s Reincarnation from 2005 also features a ghost girl with a similar impetus – revenge on any adult that wanders into the path of childhood trauma. Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s television film Séance spins a bizarre yarn of unintentional kidnapping which eventually leads to the death of a little girl – a death which, tellingly, does not occur in the source material, 1964 British thriller Séance on a Wet Afternoon. Outside of horror, Shinya Tsukamoto’s nerve-shredding drama Kotoko contains multiple instances in which the titular main character imagines the death of her infant son, often in shocking graphic detail on screen.

While the J-horror boom of the 90s and 00s may be long over, a new wave of Japanese horror is beginning to explore what the symbol of the ravaged child means in the modern world – notably, Keishi Kondo’s New Religion and Takeshi Kushida’s My Mother’s Eyes both prominently orbit the devastation left behind by the death or injury of a child, and both proudly wear their Nakata influences on their sleeves. Few things are more tragic and terrifying than the death of a child – the stark reminder that we live in an unforgiving and deeply unfair world that cares not for innocents. Horror has always held a mirror up to reflect societal fears, and if children are our future, then we are forced to reckon with the existentialist notion that our future is dark – if it exists at all. Despite the taboo of a dead child, horror audiences still seek and crave to be shocked – case in point, the widespread recent success of psychologically draining movies like Speak No Evil and When Evil Lurks. It is this darkness, this nihilism, that keeps horror fans coming back to Japanese horror, and to the haunting, humid sadness of Dark Water over two decades since its release.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OngfcStSz50

Related Articles