For a subgenre so concerned with the future, it’s only fitting that cyberpunk has continued to transform and evolve. Rooted in 1960’s New Wave Science Fiction literature from the likes of J.G. Ballard and Phillip K. Dick, cyberpunk concerns tales of urban social anxieties, technology run amok, and the post-human age. The subgenre has touched Western cinema through films such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999), becoming synonymous with mega-cities, cybernetically modified humans, and neon-drenched imagery.

However, such features don’t necessarily characterise the distinctly dark flavour of cyberpunk cinema offered by Japan. Deeply experimental and highly abstract, the films of the Japanese cyberpunk movement are defined by scathing critiques of contemporary social anxieties, which are explored through horrific metamorphosis, violent sexual imagery, and relentless dehumanisation. To understand the development of Japanese cyberpunk’s unique style, it’s essential to re-visit the early work of one of the country’s most influential filmmakers – Gakuryû Ishii.

Hailing from Hakata, Kyushu, Ishii enjoyed a wild childhood that was ultimately shaped by the region’s vibrant punk scene of the 1970s. Along with Tokyo, Kyushu was a breeding ground for punk bands and culture that swept up the teenaged Ishii and heavily influenced his artistic interests. Upon enrolling in Tokyo’s Nihon University, the fiercely independent student lived by his punk values, frequenting lectures only when in need of filmmaking equipment. The young director’s university years culminated in his thesis project, the boisterous biker gang extravaganza Crazy Thunder Road (1980). The intensely rebellious film features aesthetics that, in hindsight, can be categorised as proto-cyberpunk. The dusty, dystopian urban setting and anti-hero Jin’s boxy armour are clear precursors to later cyberpunk visual staples.

Produced on a shoestring budget and comprised of a voluntary cast and crew, Crazy Thunder Road was remarkably picked up for national distribution by studio Toei, marking a resounding success for Ishii that allowed him to embark on a far more ambitious project – Burst City (1982). Set in a post-industrial near-future, the film is a one-of-a-kind piece of authentic punk cinema. Bands fight with the police and each other, gangsters wage war on disfigured vagrants, and a pair of deranged biking brothers rage across the wasteland-like terrain.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxPPkDW3gr8

Burst City, in many respects, marks the genesis of Japan’s cyberpunk movement. The grimy, run-down, industrial environments evoke what is now considered typical cyberpunk imagery, while Ishii’s fast-paced editing and frenzied camerawork make the film a highly-charged visual feast. Perhaps one of the most important influences of Burst City on broader cyberpunk cinema is Ishii’s use of undercranking, a technique that allowed the director to produce exhilarating fast-motion sequences that would become a recurring visual motif in Japan’s cyberpunk cinema. Overbudget and incomplete, Burst City was a box office bomb that almost killed its director’s career. Despite this commercial failure, the film remains a vital work in the history of Japan’s intrinsically linked jishu eiga (self-made film) and cyberpunk movements.

While Ishii undoubtedly laid the groundwork for what would become the cyberpunk movement, one of his collaborators played a major role in the blossoming subgenre’s next evolution – Shigeru Izumiya. As well as starring in Crazy Thunder Road and Burst City, the multi-talented artist also served as art director for the latter, making him responsible for the film’s jagged post-industrial aesthetics. Izumiya would go on to direct two projects of his own in the 1980s, the second of which could be considered Japan’s first true cyberpunk film, Death Powder (1986).

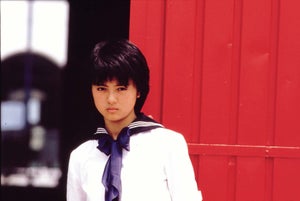

The threadbare plot of this highly experimental project involves rogue scientists, bounty hunters, and a dying android named Guernica. With Death Powder, Izumiya drove the cyberpunk movement into more metaphysical territory, focussing on grotesque visuals and innovative editing. The film prioritises graphic imagery and a heavy atmosphere over narrative cohesion to provoke a visceral reaction in viewers, an approach that would pervade Japanese cyberpunk cinema in the years to come.

It would be remiss at this point not to mention the seismic impact of perhaps the most significant piece of Japanese cyberpunk cinema, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988). Adapted from Otomo’s own 1982 manga, the film almost single-handedly commercialised anime in the West and remains Japan’s most recognisable cyberpunk export. The Blade Runner-esque cityscapes and Cronenbergian body horror have influenced both cyberpunk-inspired anime like Ghost in the Shell (1995) and broader cyberpunk cinema at large.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShJvheZHXdI

As the cyberpunk movement raced towards the 1990s, the emergence of two independent filmmakers saw the subgenre transform once again. Shinya Tsukamoto and Shozin Fukui are two names that are deeply ingrained in cyberpunk cinema, and for good reason. Their early films feature staple characteristics of Japanese cyberpunk works; Tsukamoto with grotesque metamorphosis in Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) and Fukui with brutal dehumanisation in both 964 Pinocchio (1991) and Rubber’s Lover (1996). Both filmmakers present scenes of intense violence and technology-induced mutilation, which play out against oppressive urban backdrops.

As with Death Powder, these films are innovative in their presentation, featuring lightning-fast editing, claustrophobic camerawork, and abrasive visuals. Fukui’s films, in particular, are exhausting audio-visual assaults filled with blood, puss, and agonising screams. While Tsukamoto would get his flowers for Tetsuo and its first sequel, Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992), Fukui’s films remain obscurities, which is oddly apt given their counter-culture themes and underground aesthetics.

The characteristics and aesthetics of Japanese cyberpunk cinema aren’t entirely foreign to the West, as seen in its visual and thematic similarities to David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). Even Cronenberg’s most recent film, Crimes of the Future (2022), explores a world that has surpassed human illness, making way for rapid and extreme evolution. However, the overly-polished aesthetics of Blade Runner 2049 (2017), Altered Carbon (2018-2020), and other similar modern cyberpunk works lack the roughs-around-the-edges that make Japanese cyberpunk cinema so affecting.

The cyberpunk movement marked a brief but significant spell in the history of Japanese cinema, one that saw the continued rise of independent filmmakers who dragged the country’s film industry through the abyss. The movement is bookended by Gakuryû Ishii, kickstarted by the proto-cyberpunk aesthetics of Crazy Thunder Road and concluded with his impromptu ode to punk cinema, Electric Dragon 80,000 V (2001). Evoking the electrifying punk aesthetics of his early projects, the film more represents a return to the director’s earlier style of filmmaking than an evolution of the cyberpunk genre overall.

In both the East and the West, cyberpunk cinema will continue to evolve, particularly as we tumble further into a technology-driven world. However, as of today, Japan’s live-action cyberpunk films of the late 20th century still represent the endlessly fascinating subgenre in its purest form.

Related Articles