It’s tempting when we think about the representation of teens in 70s US cinema to default to earlier that decade when the impact of things like the Vietnam War and Watergate exploded in the public imagination. Such epoch-defining moments impacted not just the everyday lives of so many people at the time in the US and abroad, but became broader cultural, social and political lenses through which the country saw itself anew.

Yet looking at films like Jonathan Kaplan’s Over the Edge that were released much later in the decade, while we can still see the bomb blast radius that spread from these earlier events, we simultaneously find ourselves drifting irreversibly towards a new phase. 1980s America was above all else marked by the presidency of one-time Hollywood star Ronald Regan who personified a shift towards a new kind of conservatism that left the free-and-loose radicalism and hippy ethos of the 1960s long behind as a distant memory.

Just like the kids in Kaplan’s film themselves, this was a generation that found themselves stuck in the middle of nowhere, adrift between these grander historical moments. The fictional housing estate of New Granada is not just a place, it’s a state of mind: a fake, constructed, imagined ideal which simply left kids behind. Too young to fight in Vietnam or to be a part of the counter cultural explosion that marked youth culture earlier in the decade, there was nothing left to do but get high, get in fights and drift.

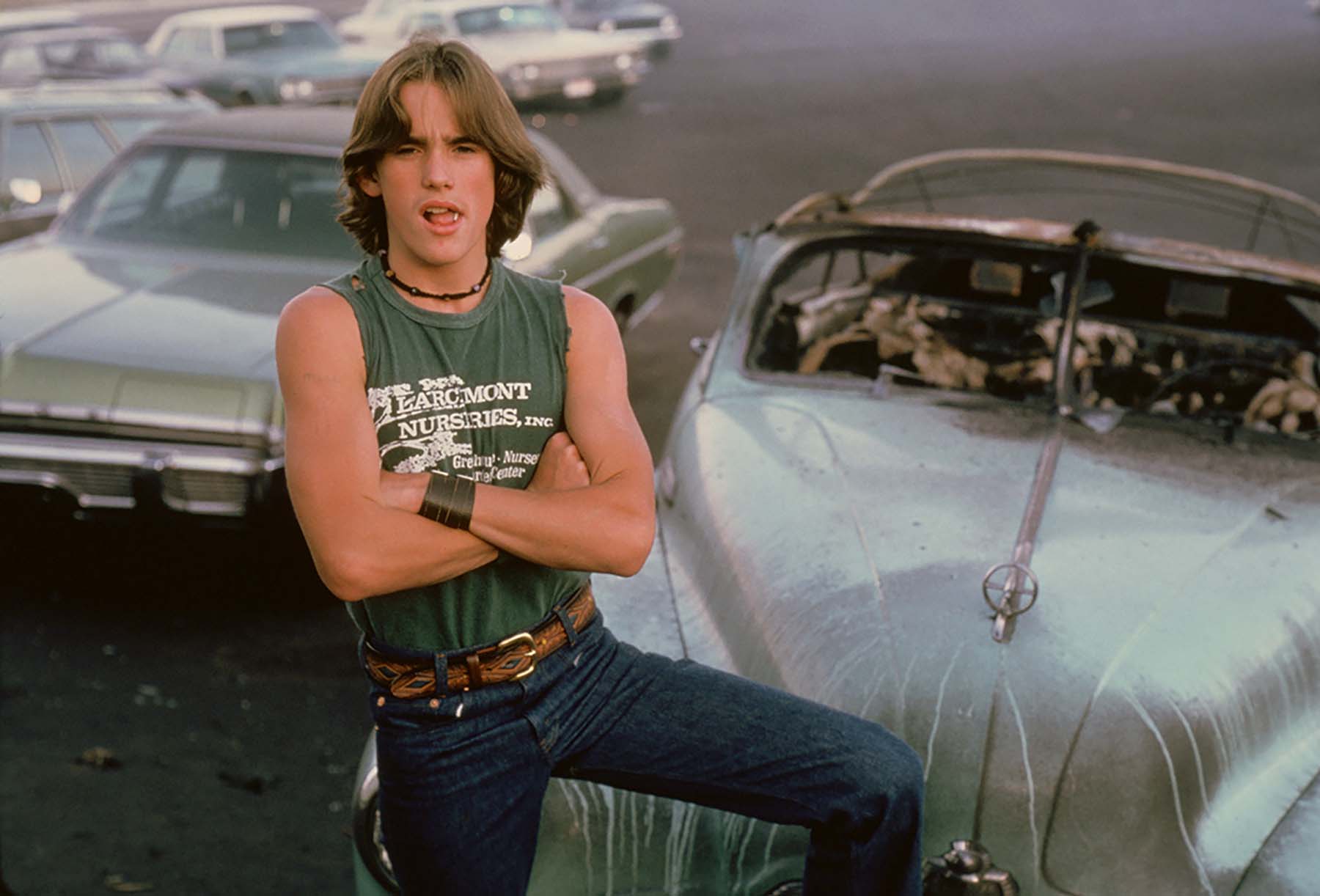

With Carl (Michael Kramer) and Richie (Matt Dillon) at the centre of its tale, Over the Edge follows a group of increasingly frustrated, bored teens who are seen by the adults in their community primarily as a problem to solve. They drink, fuck, take drugs and wander the streets, until the police harassment that plagues them escalates, culminating in an act for which the kids is the last straw.

The power of Over the Edge is just how explicitly it builds the alienation of this generation into the literal infrastructure of its small community, a microcosm of North America more broadly. The planned drive in and bowling alley? Forget it, the town will make more money if that land is re-zoned for industrial use. Bored kids who are consistently hassled by the cops starting to kick back? Let’s introduce a 9.30pm curfew. The powder keg of Over the Edge spoke not just of New Granada, but of an in-between generation of human hand grenades, isolated, bored and ignored, with nothing else to do that look for the perfect place to explode.

For many, Over the Edge is worth it just to see an early entry in the fledgling directorial career of the great Jonathan Kapan or an excuse to watch 15-year-old Matt Dillon strut around in glorious defiance wearing a crop top, a marijuana leaf belt buckle, and a sneer. And, to be fair, these things alone are enough to make the film an extraordinary viewing experience. But reflecting on its curious historical moment, the bigger picture of intergenerational flux sets the scene across which Carl, Richie and their friend’s story is ignited.

Juvenile delinquency films were of course all the rage in the 1950s especially, with all its wild ones and rebels without causes. Over the Edge updates who it sees as the villain here with almost clinical precision, exposing just what is at stake when greed rather than good governance dominates suburban planning specifically. As the text which opens the film notes, Over the Edge was inspired by true stories, and critics have identified a case in California’s Foster City in 1973 as exemplar of this, where a youth crimewave reduced the idealised suburban dream of the 1950s to little more than a naïve fantasy. This incident and others like it would echo throughout the decade, and were fictionalised in the events that take place at New Granada.

Generationally, the film’s troubled teens are what are somewhat awkwardly known as “cuspies”; straddling the line between late Baby Boomers and early Gen X-ers, if they seem stranded and lost then it is perhaps in more ways than one. While research for the screenplay began as early as 1973 (which would have made the kids very much Boomers), by the time it hit the screen in 1979, there was a shift to a different generation altogether, and we feel it in the film. As we see in the movie, even these early or proto Gen X-ers were the children of parents focused more on their careers than their kids, for a variety of reasons.

This was the heyday of the so-called latchkey kids, young people left very much to their own devices as the role of women in particular began to shift due to the social and cultural changes brought on by second wave feminism. Women were able to focus on careers because they finally weren’t being pressured to be housewives, and the divorce rate rose in large part because women realised they didn’t have to stay in shitty, unsatisfying marriages. But with many men still stuck in the more traditional headset and not ready to pick up the slack, it meant kids such as these were often left to their own devices.

There is something timeless about the youth-gone-wild trope which places Over the Edge on a long historical trajectory of stories about lost teens looking for connection, and finding only trouble in return. But when compounded by infrastructural and governmental neglect such as we see in New Granada and marked by the specific generational ennui of its specific historical moment, the meaning of the film’s title becomes apparent: of course these kids are pushed over the edge. Where else are they going to go?